| Mathew A. Wyman |

The legal structures underpinning land-control deals can be confusing. We turned to a residential transaction expert, attorney Mathew A. Wyman, a partner with Cox, Castle & Nicholson LLP in Los Angeles, to sort it out.

Feasibility or "free look" period: A feasibility period often is called a "free look" period, usually of 30-120 days. You often see a feasibility period in the context of both an option agreement and a purchase/sell agreement. The buyer then has the right to inspect all aspects of the property and do his or her own underwriting and financial market study. If the buyer dislikes what he or she sees, then the buyer can send a disapproval notice. The money put up by the buyer usually is returned. Thus the term free look.

Joint venture: Under a typical joint venture, the owner agrees to put the land into a separate entity or company in which a builder/buyer is a partner or member. Taxes can cause a problem for the landowner. If a seller just sells land, there is an immediate taxable gain at the capital gains rate of about 18%. If the seller decides instead to contribute that land to the builder in a joint venture and participates in all of the profits, the seller gets taxed as ordinary income - as much as 40%.

Loans as consideration: The builder/buyer sometimes agrees to loan money to the landowner and then has a conversion right to turn that loan into an equity position in a partnership or a back-end option to purchase. It also gives the buyer the right to tie up that property, do feasibility analysis and maybe start processing entitlements.

Long escrows: The distinction between options and purchase agreements is, in many ways, form over substance because you can structure a purchase agreement with a long escrow period and a small good-faith deposit. The good-faith deposit equates to an option consideration. A long-term escrow period equates to an option term.

Management agreements: If a property is bigger than a builder wants to buy, the builder can offer to enter a management agreement to process or entitle the land. The builder gets paid a fee and incentive to create additional value and gets the right to purchase lots as they come online.

Options and option agreements: A right but not an obligation to purchase land, usually characterized by an option payment or option consideration paid upfront. Options give buyers time to decide whether to buy the property. If an option holder elects not to purchase the property, the option consideration is forfeited to the seller. To execute the option, notice to the landowner must be given before the option term expires.

Right of first refusal: Rights of first refusal are another way to control land. A buyer can go to a landowner and offer to buy a 500-acre parcel, but the seller might hold back the last 100 acres. So the buyer might offer to purchase the 400 acres with a right of first refusal to purchase the last 100-acre piece whenever the owner decides to sell. A right of first refusal tends to be granted along with an existing option or a purchase/sell agreement.

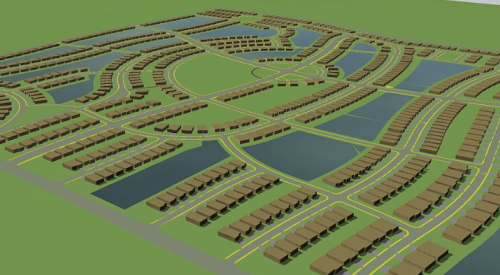

Rolling land options: The most typical option structure grants the ability to take down parcels as you go. A deal for 100 acres might allow purchases of 10 acres at a time. Usually there is a specified period of time when you have the right to exercise a rolling option. If you don't exercise it, you usually lose the right to exercise any of the subsequent parcels.

Takedowns and takedown schedules: Rolling options sometimes are called scheduled takedowns. Exercising the first rolling option means taking down a phase of land in accordance with a takedown schedule.