For the past decade, architects have used 3D modeling and visual simulations to map out floor plans and engage clients in virtual walkthroughs of new-construction projects, and thanks to new technological advancements, virtual reality (VR) is being introduced to young architects before they even enter the professional world.

In fact, the recently developed SKOPE VR, a system for immersive interaction within a 3D virtual learning environment (VLE), is being used to teach students studying architecture, engineering and construction (AEC). With the capacity to train future generations of building professionals and improve designs by those already in the field, VR is becoming an increasingly valuable tool that will alter the way architecture is taught and executed for decades to come.

The paper "SKOPE VR: A Collaborative Virtual Reality Environment for Learning and Training" by Shahin Vassigh and her colleagues explores the educational process, benefits, and challenges of VR in AEC education.

SKOPE VR as an educational resource

SKOPE VR is a collaborative VR environment that allows learners to interact with virtual objects, environments, and scenarios common on the jobsite by simultaneously joining the same program to manipulate the virtual space in real time. By donning a VR headset (complete with corresponding touch controllers), students can navigate through a building’s floor plan or construction site, interact with objects, and participate in simulations and scenarios designed to teach specific skills as determined by an educator.

For instance, a virtual walkthrough of a building equips the viewer with an “almost x-ray vision,” Vassigh says. That technology enables students to see through the walls to examine structural components, look through the ground plane to see the building foundation, and look through the ceiling to examine mechanical systems.

Navigating SKOPE’s virtual environment relies on a “pointer” tool, for movement and interaction, and a “hub,” which the paper’s authors describe as the “centralized point of experience for the user.” Through the hub, users are provided with an “appropriate experience.” The paper reads, “For example, let’s assume we want to find out more about a 3D cube in a virtual environment. Once selected by our pointer as information of interest, our hub will display relevant information to have the appropriate experiences about the selected object.”

The Pointer serves as a tool for movement around a Virtual Learning Environment (VLE).

Image: Florida International University

The “relevant information” Vassigh’s referring to is organized into three panels: the map panel, the options panel, and the info panel. Each panel provides insights relevant to its descriptor. Through the map panel, students can see location information, both as it relates to themselves and interaction options throughout the VLE. Through the options panel, users gain access to the potential interactions and experiences available relative to a specific object. And through the info panel, students are given information relative to the intended overall experience. “Building new knowledge based on previous knowledge and experiences can be tricky in a virtual environment,” Vassigh writes, “so the Info Panel aims at reducing this inherent complexity while improving the user learning experience.”

Benefits of 3-D VR navigation

Unlike a classroom setting, SKOPE VR provides learners with (virtual) hands-on training for a more realistic view of complex concepts and scenarios. Instructors can monitor the learners' progress, provide feedback, and adjust the learning experience to meet the needs of their curriculum. The collaborative nature of SKOPE VR also allows learners to work together within the virtual landscape, mirroring a real world jobsite with allocated tasks and responsibilities.

“Consider a student walking around a virtual building able to interact with objects within the environment.” Vassigh writes, “She can touch a wall and activate an animation showing its construction process, access metrics on the building envelope’s thermal resistance, learn about the material properties used in its construction, and get information on the cost of its assembly.”

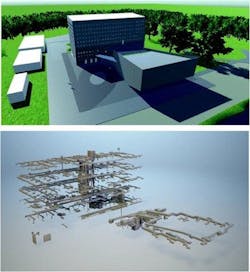

Displays of user experiences viewing the Florida International University SIPA building

Image: Florida International University

Vassigh adds “students can change the season or the date to observe heat loss and heat gain through building walls, visually locate thermal breaks, and gauge natural lighting of the building interior at different times of the day.” Those capabilities aren’t offered in a traditional classroom setting, and even on a jobsite, that training would require learners to wait months to observe seasonal changes.

Also, becauseSKOPE VR isn’t a physical learning environment, it’s potentially safer than an actual jobsite. Construction students can operate machinery and interact with equipment in a harm-free environment.

In addition to increasing safety and providing a more immersive learning experience, SKOPE VR also offers users flexibility in terms of scheduling and location. The virtual environment can be accessed from anywhere, at any time, making AEC education and training more accessible to a wider range of learners.

Challenges of SKOPE VR

While SKOPE VR offers many potential benefits for learners and educators, the introduction of any new technology inherently presents a fair share of challenges, as well. Users, for instance, mayface a learning curve to learn how to effectively navigate the hand tools and information hub, meaning students may need education on SKOPE VR before they can be educated via it.

Though still in the testing stages, SKOPE VR is designed to be widely implemented in AEC classrooms where a Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) can be paired with standard curriculum.