Homes are getting tighter, which is a good thing since half of all residential energy use goes to heating and cooling. Buttoning up the building envelope is a key strategy for boosting a home’s energy efficiency.

But airtight homes have a downside: Everyday activities such as cooking and cleaning can cause pollutants to build up in living spaces. For this reason, many states and energy programs require mechanical ventilation in new homes.

The national standard for mechanical ventilation is ASHRAE 62.2. Developed in part with research and funding from the Department of Energy’s Building America program, this standard sets minimum requirements for airflow rates for ventilation equipment in residential buildings, and it has been adopted by many states and home performance programs, including Energy Star.

Past Building America studies had shown that mechanical ventilation can decrease concentration of contaminants in the home such as formaldehyde. But until recently, very little was known about how these systems perform in the real world. What little field data there was revealed that mechanical ventilation systems in many new homes often don’t meet ASHRAE standards. In some cases, there were installation or maintenance issues, in others, home occupants weren’t using the systems correctly—or using them at all.

Initial Field Studies to Monitor Ventilation Use and Indoor Air Quality

In 2016, Building America launched a field study of 70 newer homes in California, during which researchers from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory monitored indoor air quality (IAQ), ventilation use, and occupant activities in all of the homes for one week.

When field teams first arrived at the homes, they found that only one-quarter of the mechanical ventilation systems were turned on. During the test week, most of the homes’ mechanical systems met the state’s airflow requirements, and concentrations of key pollutants such as formaldehyde and particulate matter generally stayed below recommended thresholds set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and state agencies.

RELATED

- Energy-Efficiency Road Map: Whole-Building Envelope Sealing

- Indoor Air Quality Road Map: A Smart Range Hood

- Why Pay Attention to HVAC Faults? Energy Efficiency, for One Thing

In California, Title 24 has required mechanical ventilation in all new homes since 2008. But the DOE wanted to know about homes in other regions: What differences are there in the types of systems installed? How are occupants using them? and What are the pollutant levels in the homes?

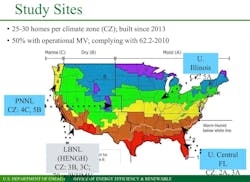

To answer these questions, Building America launched field studies in four climate zones. The Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) tested homes in cold and marine climates in Colorado and Oregon, while Florida Solar Energy Center (FSEC) investigated homes in mixed-humid and hot-humid climates in the Southeast.

“The overall focus was to characterize mechanical ventilation systems in newly constructed occupied homes,” says PNNL senior building scientist Chrissi Antonopoulos. “We wanted to look at how occupants used their mechanical ventilation systems, the state of the systems, and what people knew about the systems in their homes.” The researchers also monitored indoor air quality by tracking concentration of several pollutants.

While not all of the results have been published yet, researchers report both good news and bad: on the one hand, mechanical ventilation systems work when installed and used correctly; on the other hand, these systems often are not installed or maintained correctly and many home occupants don’t use ventilation systems as intended, in fact, some don’t even know they exist.

Monitoring Home Ventilation Systems and Indoor Air Quality in the Field

The studies followed similar protocols. First, technicians visited each home to set up equipment, which included both indoor and outdoor monitoring stations. Among other things, they installed sensors on windows and doors, radon samplers in the basements and lower levels of homes, and anemometers on fans and registers so they could tell when exhaust fans were being used.

The researchers monitored pollutant concentrations in the homes for one week. Occupants were asked to go about their lives as they normally did and to keep activity logs documenting when they were cooking, how many people were home, and when they used their ventilation systems. Some homes were monitored for two weeks: the first week with the ventilation system operating; the second with the system shut off.

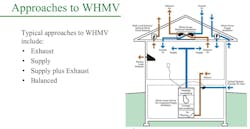

There were regional differences in the types of mechanical ventilation systems being used. For example, exhaust systems were common in Colorado and the Southeast, while central fan integrated supply systems were more prevalent in Oregon. These central fan systems use a dedicated fan to introduce fresh air into an HVAC system’s return plenum.

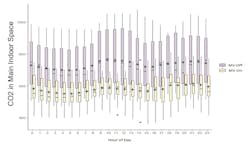

As with the California study, researchers found that the systems effectively reduced indoor contaminants. “The most significant finding was that CO2 decreased when the systems were operating,” Antonopoulos says. “CO2 is an indicator of human activity and an important indicator of what’s happening inside the home.”

The homes in the Southwest also showed lower CO2 levels and less variability in CO2 concentrations, says Eric Martin, program director at FSEC, which led field studies in Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida. The homes his team monitored also showed marginal improvements in concentrations of radon, particulate matter, and formaldehyde when mechanical systems were active, though formaldehyde levels were low to begin with, compared with older homes built before state and federal emissions standards for wood products such as particleboard and MDF were established.

Oregon and Colorado: Whole-Home Mechanical Ventilation Resulted in Lower Carbon Dioxide Levels in Field Study Homes

“I think the results have shown that source control—specifically for formaldehyde emissions—can be effective,” says Iain Walker, building scientist at LBNL. “This should encourage further development of standards and regulations that reduce emissions from building materials and furnishings.”

The Missing Link in Home Ventilation Efficacy: System Users

Just as there were regional differences in the types of ventilation systems installed in homes, there were also differences in how occupants used the systems. “We found that most of the homes in Colorado and Oregon were capable of meeting the standard,” Antonopoulos says. “Where they were really deficient was in operation.”

In these states, just 14 of 40 households knew how to operate their ventilation systems, and just 26 of the systems were properly labeled.

There were also regional differences in how occupants used—or didn’t use—the ventilation equipment in their homes. “In Colorado, a lot of mechanical systems were operating,” Martin says. “In the hot-humid climate, barely any were operating or even operational.”

Cooking activities, especially when ventilation isn’t used or is absent, are a major source of indoor air contaminants.

In Florida, the airtightness threshold at which mechanical ventilation is required is tighter than the national standard. “We allow homes to be leakier,” Martin says. “There’s an aversion to bringing in outside air, and to do it in a way where humidity might be managed is somewhat expensive compared to other approaches.” Builders and contractors are reluctant to install systems that bring in outside, humid air, he adds, as it could lead to mold growth or comfort issues.

In general, homeowners are not being educated or made aware of the mechanical ventilation systems in their homes. Martin found that occupants with central fan integrated supply systems didn’t understand that the systems were meant for mechanical ventilation and they didn’t know how to operate them.

RELATED

- For Better Indoor Air Quality: Build Tight and Ventilate Right

- Breathe Easier—Healthy Homes Go Mainstream

“If someone doesn’t know they have a system, they’re not going to be using it,” Antonopoulos points out. Similarly, if controls aren’t clearly labeled, occupants won’t understand that the system is intended to stay on all of the time. This is especially a problem for simple continuous exhaust systems such as bathroom fans, which are easy to turn off.

“ASHRAE is really explicit; the manual override switch needs to be clearly labeled,” Antonopoulos says. Such a label should explain that the switch controls the ventilation system and that it should be left on at all times except when outdoor air is severely contaminated—for example, from wildfire smoke.

Next Steps for Better Home Indoor Air Quality

The indoor air quality field study has helped illuminate issues that, if addressed, could help these systems function optimally, while helping to create healthy and comfortable indoor spaces for occupants. The researchers’ findings have important implications for ASHRAE 62.2—in particular, the importance of intuitive controls and clear labeling.

“In California, we found that exhaust systems—which were by far the most common approach to meeting the state code requiring whole-house mechanical ventilation—were much more likely to be operating if they had informative labels,” says Brett Singer, staff scientist and principal investigator for energy technologies at LBNL. “This led to a change in the state building code to more clearly require such labels.”

Martin says fault detection could help with some maintenance issues—clogged or dirty filters, for example. “I think where we need to go is automatic operation based on sensed information,” he adds. The degree of automation will have to be balanced with other considerations, such as the ability to shut systems off to protect homes from outdoor pollution—an issue that only seems to grow as worsening wildfires send polluting smoke far from their sources.

Singer agrees that there could be a role for sensors that alert occupants to ventilation issues, but he points out that some people ignore such warnings if they don’t perceive a problem.

The field studies show that prescribed ventilation rates work to reduce pollutant concentrations. But the homes in the study had relatively few occupants for their sizes. What about homes with more occupants? Larger households mean more cooking, more cleaning and personal care products, and more potential sources of indoor air pollution.

“We are very interested to apply a similar approach to study ventilation system performance and IAQ in homes with higher occupant densities,” Singer says. His lab would also like to investigate housing types that serve more vulnerable and low-income populations, particularly townhouses, multifamily units, and manufactured homes.

Builders can follow this ongoing research not just for their own education, but for guidance on how to communicate the importance of using mechanical ventilation systems optimally to clients. This way, their homes won’t just be more energy efficient, they’ll be healthier, too.

Juliet Grable writes about the built environment, energy, climate change, species conservation, and environmental restoration. She lives in southern Oregon.