Within the year, the International Code Council will publish the 2015 version of the International Energy Conservation Code (IECC), a set of building rules addressing energy efficiency that serves as the model for states and localities across the U.S. The standards organization, which updates the code every three years, issued the 2012 IECC in July 2011, but legislatures have been slow to adopt its provisions amid concerns about expense and complexity.

The release of a new edition will likely compel more state and local jurisdictions to revisit their current codes, which could lead many of them to implement the 2012 IECC and enforce its guidelines for additional insulation, tighter envelope and ductwork, better windows, and more efficient lighting.

“That’s really going to make builders up their game,” says Jerry Gloss, AIA, NCARB, and senior partner at KGA Studio Architects in Louisville, Colo. “The biggest difficulty is getting builders to see the writing on the wall.”

The housing industry for the most part retains a conservative approach to construction because builders must endorse a prominent, costly product and remain accountable for its performance and durability over many years. Companies that already operate at a relatively high level and make good money doing so hesitate to embrace change, especially when additional expenditures and steep learning curves appear almost certain. But builders should commit to creating higher-performing homes regardless of the potential hurdles because they will ensure their product remains competitive—and their company profitable—once a more stringent code is adopted.

The Essential Enclosure

KGA Studio Architects designed the first production home certified by Passive House Institute US. Photos courtesy of KGA Studio Architects

The shrewdest way to increase a home’s energy efficiency entails making improvements in its envelope, which can be better defined as an enclosure to account for the relationships among the building’s walls, windows, roof, foundation, and general assembly. Builders who disregarded the importance of airtightness for years now understand the role comprehensive air sealing and properly installed insulation play in enhancing comfort, reducing utility costs, and boosting durability.

Every new home built to the 2012 IECC must pass a blower door test by meeting the code’s standard for airtightness—a maximum of 3 air changes per hour (ACH) at 50 pascals in colder U.S. climates and 5 ACH in milder climates. The 2009 IECC, which established a threshold of 7 ACH, previously gave builders two options: conduct the test or complete a checklist of requirements. The 2012 version requires builders to comply with both conditions in all instances.

Upgrading the barrier between the interior and exterior environments of a home requires framing techniques that allow for more insulation so the building can attain certain R-values, especially in the walls. When installed correctly, spray foam as well as blown-in fiberglass or cellulose all represent effective and economical solutions for improving the enclosure, says Mark LaLiberte, a building science expert and leading industry consultant.

“It’s the smartest thing anybody could do and, in all honesty, the least expensive,” he says. “There is only one chance to improve the thermal enclosure and significantly reduce operating cost and potentially reduce maintenance costs as well. Doing it now is extremely cost effective.”

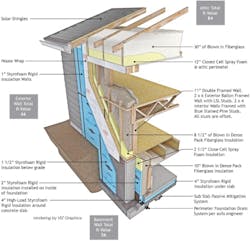

KGA Studio Architects selected a double-framed 2-by-6 wall construction for a house the firm designed for Brookfield Residential Colorado last year at the builder’s Midtown community in Denver. The project, which received a grant from the Department of Energy (DOE) because of its aspirations for Passive House and Challenge Home verification, specified pre-engineered roof and floor trusses and tried to stick with materials and methods familiar to most production builders. The outer wall was flashed with spray polyurethane closed-cell foam and the remaining depth was filled with blown-in fiberglass insulation, creating what Gloss calls a “glorified flash-and-batt system” that most production builders know how to install.

“We didn’t really incorporate any new technologies in the framing,” says John Guilliams, director of design for KGA. “We tried to use what they were comfortable using.” The firm did, however, add a layer of exterior rigid foam sheathing—a growing trend in the marketplace—to cut down on thermal bridging permitted by wall studs and reach 0.6 ACH, says Gloss. “That made a huge difference in the calculations that were done to achieve the Passive House,” he adds.

Brookfield Homes constructed a double-framed wall to ensure an airtight building enclosure.

The partnership between Brookfield and KGA created the first home intended for production building to earn certification from the Passive House Institute US. Brookfield stepped out of the typical production builder’s comfort zone when having to deal with some newer technology—triple-pane windows, for example—and received a payback on the company’s investment, says Gloss. The question now, he adds, is how the project will influence Brookfield as the builder moves forward.

New Town, Familiar Way

Photos courtesy of New Town Builders

In search of a better enclosure, New Town Builders in Denver experimented with several new techniques to improve air sealing but found many methods to be too cumbersome for the company’s trades and problematic in the local climate. The builder decided to refocus its ambition and instead concentrate on smaller means. New Town added drop ceilings to the second floor wherever there was penetration into the attic, so that any penetration now occurs in a sealed soffit area and maintains a continuous air barrier between the living space and the attic. This change, along with the addition of a new sealant, helped the company drop the average ACH in its zero-energy homes from 2.25 ACH to just above 1 ACH.

“We managed to do that with standard products and a detailed look at how we execute in the field,” says Bill Rectanus, vice president of home building operations. “We really need to watch the smallest aspects of our construction to give us the most benefit at the end when it comes to our energy rating and our ability to provide a zero-energy home.”

New Town launched its zero-energy option in 2011 with the debut of the Solaris series in Stapleton, the top development in Denver and one of the longest-running projects in the country. The builder began the design process for Solaris with the immediate goal of maximizing the insulative value of the home’s shell. The company elected to construct double-framed 2-by-4 walls with 2.5-inch air gaps for a 9.5-inch insulated cavity.

“It works well in our climate and it’s a very simple transition for our framer,” Rectanus says. “Our framer knows how to build a 2-by-4 wall; now we just ask him to build two.”

New Town Builders shifted the bearings in its frames to create a thermal break.

New Town spaces the studs 24 inches on center and staggers them between interior and exterior walls so the studs are not lined up and the insulation depth of the wall cavity is maximized. The wall, once insulated, can reach a maximum of R-34 with the aid of another tweak the builder made to gain a thermal break. “We actually shift the bearings so the roof trusses bear on the outside wall and the floor trusses bear on the inside wall,” says Rectanus, who underscores the significance of assessing the building enclosure before anything else.

“You want to make the most energy-efficient shell that you can possibly make and include high-efficiency appliances and components within it before you even get to the fancy technology of the solar panels,” he explains.

The Solaris 2, a continuation of the series that offers a zero-energy option, features just shy of 10 kW of solar on a roof that encases R-50 blown-in fiberglass insulation. New Town upgraded the HVAC in the latest edition of the Solaris series to a 16 SEER air conditioner with a 97.4-percent variable speed furnace; in Z.E.N., a series the builder introduced last fall that delivers zero-energy as a standard feature, the HVAC system upgrades to a Greenspeed heat pump. “It’s a great option for us because it uses electricity rather than gas, and we can offset that more directly with the solar panels that are on the roof,” says Rectanus, who is considering a ductless mini-split system now that the technology has evolved.

In the Air

TC Legend Homes uses structural insulated panels to frame all of its houses. Photos courtesy of TC Legend Homes

Once a builder has established an airtight enclosure, the need for whole-house ventilation requires an HVAC system capable of continuously circulating fresh air through the home in well-sealed ducts. Recovery ventilators that pull in air and condition it through a heat-exchange process have entered the marketplace, but they can be expensive. The emergence of the ductless mini-split system in particular has forced the HVAC industry, which has made its living off forced-air systems, to develop smaller and more efficient units that can be installed inside the building and naturally redistribute air.

“That’s been the biggest difficulty our industry is having—the [typical house] design doesn’t really bode well for putting the HVAC in the building,” LaLiberte says. “They like to stick the ducts in the attic, which is probably the biggest energy disaster around.”

Even if the builder opts for a more conventional system, dropping the ceilings of the home’s upper level 10-to-12 inches can easily accommodate ducts and keep them out of the attic and in conditioned space. KGA Studio Architects, however, considers the location of HVAC system to be as important as the type of system when the firm designs its house plans.

“If we do a centrally located HVAC system in the middle of the house, it’s going to be more efficient,” Guilliams says. “We don’t necessarily rely on the technology, we rely on good design to start with.”

TC Legend Homes in Bellingham, Wash., discovered using structural insulated panels (SIPs) for wall construction simplifies the design and installation process and provides automatic air sealing by merely following the manufacturer’s directions. “It didn’t take anything extra to get that really tight building envelope,” says owner Ted Clifton, who decided to frame with SIPs exclusively a dozen years ago after a drawn-out debate with his father about their merit compared with double-wall framing.

“A lot of times we’re in the city on a tight lot where adding an extra 6-to-8 inches of wall thickness would be a deal breaker,” says Clifton, who has also used insulated concrete forms (ICFs) to frame super-efficient homes but finds SIPs to be the most cost-effective technique.

In fact, TC Legend worked with SIPs to produce one of Seattle’s first true net-zero energy houses in 2011. The home achieved 0.5 ACH and cost just $112 per square foot to construct. “We eventually realized we could build net-zero houses for cheaper than most people are building regular houses,” Clifton says.

The Time is Now

New Town Builders created a building science center to help market energy efficiency.

Builders who take this opportunity to consider alternate materials and techniques for constructing high-performing homes will find themselves in a favorable position no matter when the majority of municipalities finally decide to act or which energy code is adopted. The 2015 IECC will add another performance path based on the HERS Index, an incentive for builders who can formulate their own affordable method for creating high-performing homes that score low enough per an energy rating.

One hurdle in devising the best way to construct a house, however, is how to educate the trades about new techniques after so many of them left the industry entirely during the downturn. “The biggest obstacle to getting there isn’t technology,” says LaLiberte, who also serves as president of Construction Instruction, a company that provides communication tools about building science best practices. “We’re so adept at creating great systems, but the installation is so challenged.”

In the meantime, builders such as New Town will continue to set the pace and raise the bar for a housing industry unsure about what to do next. “As the 2012 code is rolling out, we don’t have to do anything,” Rectanus says. “We’re already there, and we’ve been there for a while.” PB

Sign-up for Pro Builder Newsletters

Get all of the latest news and updates.