Architects come out of school with a ton of knowledge, except most don’t actually know how to be an architect. What does that even mean? That is the focus of Episode 75, where we discuss what it takes to “build an architect.”

A large part of our focus will be determining what that might actually mean, and how your definition of this could be different based on your interests, the type of work you do, the role you have in your office, and even the size of the firm where you practice. Welcome to Episode 75: Should Architects Do It All?

Inch Wide versus Mile Deep jump to 1:00

What is generally considered “standard thinking” or simply the thought process that goes into “how things are done” is different in small firms versus large firms and I will concede that there are pros and cons to how developing an architect. What does that even look like? If you are like most of the people I have spoken to on this very topic, the default is that you put your time in, and through time and experience, you eventually cover enough ground to become a competent architect … but this is a small firm way of thinking about the process and it was definitely my way of thinking up until about 2 years ago.

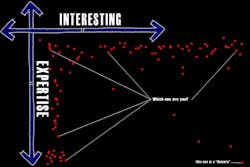

I saw a chart years ago that compared the “inch deep/mile wide” skillset which is generally considered a small firm or independent skillset that is born out of necessity and the “inch wide/mile deep” skill set which is generally considered a larger firm/ specialist skill set. The former makes you interesting but the latter is what gets you recognized … but it is almost impossible to be both things at the same time.

Early on in my career, I struggled mightily when it came to collaboration … I wanted my boss to tell me where I needed to be, NOT how to get there. The fact that he traveled on the time and I didn’t actually know what I was doing (and it was just the two of us), I had to pull out previous sets of drawings and logic my way through them and copy what those previous sets look like in order to do my job. Out of necessity, I had to work through all the technical stuff really early on in order to do what I had to do. I didn’t have someone who specialized in a particular area who could be that subject matter expert that would help me learn important considerations without having to actually live my way through the process.

Technical Skills During the Design Process jump to 6:10

This is definitely a conversation that was born out of me having sour grapes about not having my design selected for a project where 4 of us all went off into our private work areas and designed a building based on established programming requirements. When the client ultimately made their selection, my design essentially received an honorable mention and a different design was selected. This is where the sour grapes come in …

As a senior designer, there was a long list of items that I considered as part of my design, things like budget, structural systems. maintenance issues, construction sequencing, roof access, etc. and in the scheme that was selected, I feel somewhat confident that these sorts of items were not thought through, and as a result, the design was much more dramatic and definitely had a WOW factor to it (20′ cantilevered balconies can do that for you) that mine did not. The owner choose this very dramatic scheme and we all went to work reimagining the building so that those cantilevers came back within acceptable ranges, budget accommodations were made, and on and on. I will concede that it is still an amazing-looking building and I am very happy with the role I played to help add a level of technical design rigor to it, but it still kind of bothers me that we went through this process in the first place. So what does this story have to do with today’s topic? It essentially a conversation about how architects who become entrenched within a certain skill set are ultimately limited at the breadth of knowledge it takes to put a building together.

If you would like to dig in a bit deeper on this sub-topic, I wrote a post titled “Design Process: This is New for Me” in May 2020.

Office Arrangement and Desk Placement jump to 10:52

Andrew and I spent some time discussing if how the office is laid out would have an impact on how architects evolve. In small firms, this sort of thing doesn’t really matter since, by their very nature, everyone is already sitting pretty close to everyone else. In a firm where there are 80+ people in a space, there is typically some logic that is applied. This could manifest itself in any myriad of ways:

• Organized by project

• Organized by skillset/ department (design, project architect, construction administration, etc.)

• Organized by seniority

• Organized by project type (housing, office. residential, etc.)

When I first started, it was organized by skillset and designers sat with the other designers, construction administration all sat together … and I thought this was sending the wrong message. It was really convenient and there was a certain amount of groovy energy that was in the design pod (the image above shows a typical “pod”) but I felt like if you were a person who didn’t sit in the design pod, that meant that you did not have any design responsibility … which is definitely the wrong message I want to be sent.

We ended up using this pandemic to re-evaluate how the office was laid out and as a result, we blew everything up and now our goal is to build a “pod” that is made up of a mix of all project skill sets. It isn’t as easy to talk to all the team members as it now requires you to walk around a bit (which I also think is a good thing) but we are already seeing the benefit of what happens when someone from the construction administration side of the project is sitting next to someone who is designing buildings. The conversations that are now taking place are simply different.

Does Specialization Lead to Stagnation? jump to 29:21

This bit of conversation is really centered around the idea that just because I haven’t done something a million times before, doesn’t mean that I don’t have something of value to bring to the process. My typical response to this situation is the suggestion that because I haven’t entrenched myself with solving the same problem over and over again, I will bring a fresh perspective to how something is done. I also tell people that I will listen better than someone who has done this particular project before 100 times – I will pay more attention to your needs rather than suggesting that “as the expert” I will tell you what you need and the expectation is that you do what I tell you.

There has to be a moment where all parties have bought into the process – a balance between the client’s needs and my ability to understand, internalize, and direct a solution that is beneficial. Clearly, there’s a benefit to experience – nobody would deny that, but I also think that the ability to bring a new perspective to a process is critical in our profession. I typically believe it comes down to communication except when it comes to public work where you frequently don’t even get a chance to talk to the client since the process is almost exclusively associated with past experience. You never have the chance to truly introduce the team, talk about how you are going to approach the project, how are you going to approach the solution, how you are going to engage the entire project team … all of this is mitigated when the selection is solely based on a package of past projects that explain what you’ve done in the past.

Would you rather? jump to 49:06

I haven’t thought about eliminating a “Would You Rather” question before but this one got me close. On the surface, and depending on your gender, it’s an easy answer … but it doesn’t take long before the wheels start flying off.

Would you rather be 7′-0″ tall or 4′-0″?

I feel extremely positive that I know given these two options, which one a man would choose … I don’t think Andrew even spent 10-seconds debating it. This is admittedly one of the easier questions that we have tackled in a while – but once we start deviating the parameters a bit, things get uncomfortable and I ended up asking this question to a handful of women that work in my office to see what their response would be …

Ep 075: Should Architects do it All?

Of all the topics we have discussed this year, this one might be the most interesting and have the most area to cover. This conversation could easily pivot from “Should Architect do it All” to “Why Architects Should do it All” or “Can Architects do it All?” While there is just a bit of semantics between the two, there is a fundamental difference between how the process of educating an architect within a professional environment happens. When I was a bit younger, and still working in small offices, I remember having a conversation with a friend of mine who runs the architectural component within a very large construction company. He had gone the route of working in a large firm for his entire career and was an extremely knowledgeable and capable architect while I had done pretty much the exact opposite and as we sat down for a visit, we both looked at the other with a bit of envy. He saw what I was doing – the variety of the projects and my all-encompassing role on those projects – while I was looking at him with admiration about how knowledgeable he was in an area where I barely could hold a conversation. It was not without some humor that we both recognized this and dismissed it all just by thinking that the grass is always greener on the other side …

But is it? I’d be curious as to what others think on this subject because I don’t believe there is a right or wrong answer, there’s just what you know and what you think.

Cheers,

Life of an Architect would like to thank Steve Weyel with BILCO for joining us today. For more information on BILCO’s Thermally Broken Roof Hatch, just visit bilco.com. You can also call (800) 366-6530 to speak with a Bilco representative.