At first, many home builders may dismiss Dr. Bo Kasal as nothing more than an ivory tower windbag full of hot air.

If you build along the coast or in other high wind prone areas of the country, you may find it valuable to give him a more thoughtful hearing. The North Carolina State associate professor of wood engineering and mechanics has several years of high profile, NAHB and HUD-sponsored research behind him when he says that building codes and home building practices in much of the U.S. are woefully out of touch with state-of-the-art technology for resisting hurricane force winds.

The bad news, Kasal says, is that the minimal measures most builders are taking do meet code requirements, but those standards represent a "bare bones" approach designed to protect "box-type" houses, not the larger and more complicated homes now commonly built in many markets along the coasts.

"It's assumed that these houses are safe," says Kasal, "but past performances show deficiencies in construction practices and code enforcement."

The good news is that, based on research and testing he directed this past summer in Melbourne, Australia, Kasal advocates builders be given broader leeway in designing high wind area homes. He wants building codes to be "performance-based" rather than prescriptive. However, under Kasal's proposed approach, building plans would have to be approved by structural engineers.

"Our goal is to make the building perform better when buffeted by such natural forces as sustained winds or ground motion caused by earthquakes," he says.

Kasal believes performance-based standards would encourage home builders to use construction strategies that add to the structural integrity of the building. He says freer design criteria would encourage innovation, such as use of interior load-bearing walls and clearly established pathways to transfer load forces to the foundation. He also believes it would open the door to use of new materials and building technologies.

Kasal is helping to lay the foundation for improved residential construction methods by designing a computer program that models how natural forces affect a building's structural integrity. He's refining the program based on tests last summer of a specially-designed building in Melbourne, Australia.

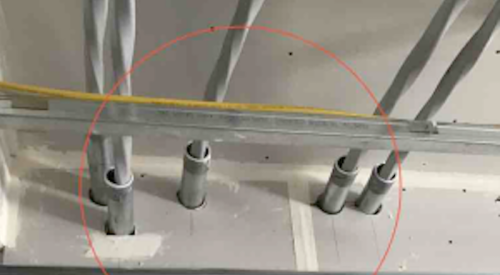

The L-framed, single-story, ranch-style house was fitted with instruments to measure how loads, applied by hydraulic presses (simulating natural forces), were distributed through the structure. The goal of the project, sponsored by NAHB and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, was to find out how the forces "traveled" to the building's foundation, and how parts of the structure, such as load-bearing beams and connecting walls, held up under lateral displacement of the building caused by those forces. The four-year project will be completed in 2001.

The Structural and Materials Division of NAHB Research Center organized the research. Director Jay Crandell says the study was commissioned because current engineering design methods for homes are not as efficient as implied by their incorporation into building codes across the country.

As suspected, the whole-building test data gathered in Australia indicates that current design methods can produce very erratic results, tending to be either uneconomical or unsafe or both. In many cases, the error for a single shear wall can be more than 50% in terms of the calculated design load, Crandell says. "This type of observation has bewildered many researchers and remains an uncomfortable mystery to code developers and engineers," he says.

In light of the tremendous volume of housing construction now underway in coastal areas, Kasal believes an investment now in developing and implementing performance-based codes will pay off when the next major hurricane hits the U.S.

After all, he says, Hurricane Andrew caused 61 fatalities and $26.5 billion in property damage in Florida and Louisiana in 1992. And Hurricane Hugo caused 86 deaths and $7 billion in damage in South Carolina three years before that. Today, many more people live in threatened areas than a decade ago. "The government usually mitigates after the disastrous damage has occurred," Kasal says. "Why not spend a fraction of that amount up front and reduce the impact? The social impacts of hurricanes are not the same as they were 50 years ago, when population density along the coastline was much lower. It's only going to get worse, not better."

Will performance-based building codes add to costs? Kasal doesn't think so. He believes such standards would actually reduce the amount of material used to build a home. Building better requires only the application of intelligence and innovation, not more money, he says.

Also See:

Tests in Austrailia Lead to U.S. Innovation