What Is the Cost of Quality Construction?

I hear and read all the time that you can’t quantify quality. It’s an ethic, not a number; an abstract goal that doesn’t show up on the budget. Quality is in the eye of the beholder.

To be fair, there’s no consensus about the definition of the word quality in the housing industry, running the gamut from callbacks to the customer experience. As such, there’s no standard or formula, to place a dollar amount on quality. Until now.

That number is $4,919.

This is the amount that Theresa Weston, Ph.D., a senior research fellow at DuPont Building Innovations, found to be the average amount set aside per house by 13 publicly traded home builders to cover the cost of warranty work. Add construction defect litigation and that per-house reserve balloons to $22,278. Once I got over the shock of those figures, I decided to do something about it. I wanted to address our industry’s penchant for paying out huge sums of money for substandard work, on the front end (the cause) and the back end (the effect). If builders are so willing to throw good money after bad, maybe it’s for lack of a different model. Or any model.

I envisioned a road map that enabled builders to objectively measure the key metrics of construction excellence to the point of their respective and collective budget impact … and then address inefficiencies (read: unnecessary costs) until a moderate investment in good quality wiped away the excessive expense of poor quality. I wanted a way for builders to understand what they spend and why.

We call that road map and formula The Cost of Quality.

An Attractive Return: Define Building Quality and Its Costs

Let’s get right to it: What if I said you could save more than $7,200 per house by investing $1,200 up front in delivering better quality? You heard me: a 600 percent return. Maybe a little less, maybe a little more, and likely not all at once, but certainly better than breakeven. Multiply that number by your annual closings and it probably looks pretty attractive, or at least good enough to keep reading.

To get there, we needed to define quality and its costs. My team and I scoured industry sources for data, finding enough pieces from NAHB’s annual “The Cost of Doing Business Study,” the “New Home & Building Materials Warranty Report” from the Warranty Week website, and customer satisfaction correlations from Avid Ratings, among others, to start filling in the puzzle.

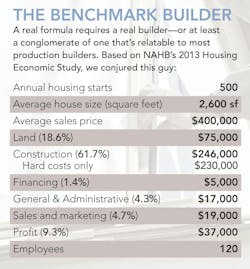

Those references also helped us create a builder profile for benchmarking purposes as we fleshed out the formula (see The Benchmark Builder, below). We then brainstormed 29 metrics, from rework to customer referrals, and sorted them into eight buckets:

- Value Engineering

- Jobsite Waste

- Construction Oversight

- Cycle Time

- Cost Overruns

- Employee Satisfaction

- Customer Engagement

- Warranty

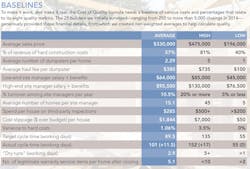

For each of those buckets, we defined the parameters and added a Cost of Quality measure—for example, the bottom-line impact of a 1 percent increase in overall customer satisfaction or a 0.5 percent reduction in hard costs. Then we dug deeper, initially surveying 21 production builders representing nearly 10 percent of all new-home closings in 2014, to establish a baseline for each metric and for others, such as the average new-home sales price, percentage of revenue spent on construction, and budget slippage.

At that point, we felt ready to plug in the numbers and do some math, taking a decidedly pragmatic approach bordering on self-doubt and cynicism. When a number came up rosy, we lopped off a percentage just to be safe or looked for ways to discredit it. When we made assumptions, we solicited sanity checks from our production builder clients. In the end, we felt confident in the formula and the results.

The 600% Commitment to Construction Quality

While the Cost of Quality road map flips the script from back-end reserves to up-front investments in quality with attractive returns, it’s only a guide. Making the assumptions a reality takes work, and likely will disrupt your operations, accounting, and comfort with the status quo.

Those are real risks, but consider the alternative: If you don’t have every single aspect of quality defined for your company, someone—including customers and regulators—will set it for you. It is incumbent on builders to set expectations, manage them, and deliver on them. Doing so, however, doesn’t require more “quality checks” during construction. In fact, the formula calls for fewer internal inspections, not more of them.

That’s because there are smarter investments to ensure accountability: educating subs on your standards and holding them accountable. The result, we’ve found, reduces internal inspections, cycle time, and rework costs, each of which has an impact on the bottom line.

Another cost—one that builders notoriously and historically miss—relates to setting and managing customer expectations. “In some areas, we have to use plastic plumbing pipes, and homebuyers may not see that as equal or better quality (to metal),” says Doug Campbell, VP of customer care for CalAtlantic Homes’ Southern California division, adding, “We have to show confidence in changes that add value and share that expectation with the homeowners”—or suffer potential backlash, financially and otherwise, after occupancy.

Those experiences speak to where builders start down the Cost of Quality path. While our calculations pencil out to $7,250 in total savings across the eight categories (see How We Got There, opposite), your math will vary depending on your costs, efficiency assumptions, and other factors, including your comfort level.

But here’s the thing (and it really doesn’t matter where you start): Once preventive quality becomes your new normal, your initial investment can pay even greater dividends. “A focus on quality becomes a desire to constantly want to improve your company because you’re invested in it,” says Jasen Torbett, operations manager for Shea Homes’ San Diego division. “It feeds on itself.”