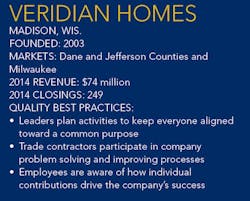

NHQ Gold Award Winner: Veridian Homes

Among the many strengths NHQ Awards judges noted about Gold winner Veridian Homes is that the builder’s processes are so well defined and measured that those details perpetuate its culture of systemic improvement.

The company’s pursuit of continuous improvement has pushed the delivery of customer satisfaction beyond merely fixing a defect discovered during a home inspection. Veridian employees delve into whether the punch-list item was a one-time mistake or a breakdown in the system.

“We try to move a lot of our energy into prevention, so we can do a lot less inspection,” says David Simon, president of operations for the Madison, Wis.-based builder. “You can have a team of inspectors follow your trades and your super, but that’s a lot of money to spend on inspections. Over the years, we’ve trained our people to write down how we do things the Veridian way, share our scopes of work with the trades, develop checklists, and collect the data, so you can have a reasonable understanding of what has to be done. That’s allowing us to reduce our inspection time and significantly lower what we have to correct in the field.”

The Gold is Veridian’s second top NHQ Award—the builder won in 2006 and took Silver in 2005. Veridian was formed from the 2003 merger of two long-time Madison builders, Don Simon Homes—a Silver and Gold winner during 2001 and 2002, respectively—and Midland Builders. The combination produced the largest builder in the state, with plans to close 600 homes going into 2006.

But the Great Recession forced the company to lay off many employees. The staff, which had boasted more than 100 full-timers during the merger, dwindled to fewer than three dozen people by 2012. As if the downturn didn’t inflict enough pain, Veridian’s bank filed a $16.4 million foreclosure lawsuit that same year and threatened to auction the builder’s undeveloped land to pay off mortgage debt. The lender relented several months later and dismissed the lawsuit.

Simon has been reengineering his companies as far back as the 1990s using a form of open book management to share performance indicators with employees for setting goals and tracking execution. So the recent downturn offered an opportunity to work on the business and pursue continuous improvement. For example, Veridian gave employees even more tools to think like owners by educating them about how their activities can affect the income statement and the balance sheet.

Collaborating with subcontractors is another reengineering activity. By 2007, Veridian funded quality-management certification training for 80 of its trade partners, and through the recession until today, the builder has maintained quarterly and semi-annual trade partner council gatherings to discuss hurdles in the field and find solutions.

In 2008, Veridian formed a What’s Up team; a small group of employees who meet weekly to discuss and address customer concerns. The team often can unearth and start resolving a customer experience problem before the issue surfaces in a monthly customer satisfaction survey.

“Any time you’re getting survey information, that is history,” Simon says. “ We want to have that history as current as possible. So if there is something that our customer is experiencing that we need to be dealing with, we call it ‘what’s up.’ What’s up with our consumer? What’s up with our process? We have a group that can quickly listen to the voice of the customer, so if we’re getting some feedback that a customer had a bump in the experience, rather than wait for that bump to follow us to closing or post warranty, we do everything in the organization right now to take care of it.”

That team is one of several customer satisfaction initiatives that prompted an NHQ judge to note that Veridian is “passionate, focused, and enthusiastic about a strong buyer experience and a well-built product.”

Another initiative is restructuring the responsibilities of its construction managers or superintendents—dubbed “personal builders” at Veridian. Previously, they managed a project for the homeowners and ran the job until closing when the clients were handed off to the customer-care team to handle warranty issues. The problem was that the customer-care team didn’t have the months of relationship and trust that the personal builder had developed with the clients since the contract was signed. Plus, no one was as knowledgeable about the house or ways to fix it as was the personal builder.

So Veridian eliminated the hand-off, created a warranty customer service help desk to take care of fixes that occur through the 12-month warranty period, and put the personal builder in charge of managing the client’s home for one year after closing. Personal builders visit the clients 30 to 45 days after closing to glean whether there are any problems and to teach them about homeowner maintenance responsibilities. They then visit again in 12 months to wrap up the warranty period and provide more education. Veridian reduced the number of projects that personal builders manage so they can take on the warranty duties. The switch cut the cost of post-closing fixes that couldn’t be directly attributed to a subcontractor by two thirds and raised customer satisfaction scores.

“The homes are being delivered with fewer defects at closing because the builder knows he has to manage this relationship post-closing,” Simon says. “It’s been a great success for us both financially and through the relationship with the customer.”

Simon has been steadily hiring since 2013 and currently employs 59 full-time and two part-time employees. After closing 249 homes on sales of $74 million last year, the company is projecting 340 closings for 2015 and $100 million in sales. The gain can be attributed to many factors, such as reorienting the business to focus on profitability and customer loyalty through product and market diversification, and more integrated planning with such practices as even-flow construction scheduling that’s so detailed, the builder can give customers a hard move-in date at contract signing. A judge noted that Veridian’s scheduling system from BuilderMT is one of its best practices.

Veridian is very data driven, collecting statistics for actual vs. estimated costs, warranty costs per home, third-party customer satisfaction scores—it even polls employees about their quality of life. But Simon says his team isn’t paralyzed by analysis because it actually does something with the information. What it doesn’t do is manage by gut reaction. Simon’s frequent adage, one that an employee actually repeated to an NHQ judge, is, “In the absence of data, you have myth.”

“When something goes wrong, I look at my system,” Simon says. “We don’t blame the employee. We blame the system or the lack thereof. If you don’t have a system, how can you say [your employees] don’t know what they’re doing? It goes back to a lack of systems or a lack of education. If you don’t document, then you really can’t have a process of improvement. So the first thing you have to do to have a continuous improvement process is you have to write things down.”

After surviving the worst slump to hit home builders, Simon’s next challenge will be steering Veridian through a cycle where skilled labor is tight and finding skilled managers is difficult.

“We’ve always been a systems- and process-oriented builder,” he says. “We’re big on documenting process and action plans and how we run our business, but now I have to figure out how to do more with less. It’s hard to find really great people to run our business, so we have to make sure our systems and processes are in the highest and best order possible. We went about this NHQ Awards application as a reason to get our playbook up to Super Bowl level.”