Architect Matthew Tills used structural insulated panels (SIPs) for the first time when he designed a home in Madison, Wisc., for himself, his wife and their two sons. Tills found that the panels were easy to work into his chosen palette of materials. Since moving into the house, he says, there has been no utility-bill “sticker shock” — which, considering the severity of Wisconsin winters, is a testament to the way SIPs contribute to an airtight envelope.

Tills, builder Tim Wood of Wood Construction, Oregon, Wisc., and Mary Burk of ACH Foam Technologies, Denver, gave DI the details.

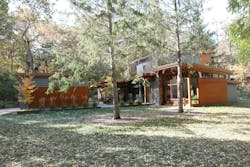

The Madison, Wisc., home of architect Matthew Tills and his family incorporates structural insulated panels (SIPs) for an airtight building envelope. To achieve a modern aesthetic, Tills specified a mixture of corrugated metal and ProdEX, an engineered wood product, for the exterior. Photo: Matthew Tills

DI: Why did you decide to use SIPs in the construction of your home?

TILLS: We wanted it to be an energy-efficient home but have a modern aesthetic to it as well. I got turned on to the idea of SIPs as I was doing some research on high-performance building envelopes. We considered insulated concrete forms (ICFs) as well as spray foam to super-insulate the house. Then we decided on SIPs because they seemed like a nice compromise between the two.

DI: How did the design take shape once you had made that decision?

TILLS: A tennis court used to be on our lot, so it’s surrounded by mature trees. We designed the house to fit the footprint of the tennis court. It’s a 2,700-square-foot, two-story home. The master suite and primary living areas are on the first floor — an open kitchen and dining area, a living room, a media room and a screened porch. There are two bedrooms, an office and a bathroom upstairs.

I had a palette of materials that I wanted to use to create a modern home with a structural timberframe feel. We did a hybrid structure that incorporates a variety of building techniques. For instance, the living room has post-and-beam framing, while SIPs were used in the rest of the house.

WOOD: All of the walls are built with SIPs as well as part of the roof. The roof panels are 12 inches thick and have an R-value of 48. The wall panels are 6 inches thick. We used two inches of spray foam on the outside of the panels, so they’re probably R-35.

DI: Were there any site constraints that impacted your design?

TILLS: Because the site is kind of low and the water table is really high, we couldn’t do a basement, so the house is slab on grade.

WOOD:

We had to tear out the tennis court and the fencing around it, which was not a big challenge, but because of the high water table we had to use bigger footings for the slab.

DI: Matthew, you alluded to a specific palette of materials. Can you elaborate?

TILLS: All of the trim and doors and most of the built-ins are Douglas fir. I like the warmth and character of Doug fir, which you typically see more of in the Pacific Northwest than the upper Midwest.

I wanted in-floor radiant heat, so all the flooring on the first level is sealed, stained concrete. It’s a little more raw than a lot of people would like. There are tongue-and-groove wood ceilings in the living room and maple cabinets in the kitchen.

On the exterior, I used a combination of corrugated metal and an engineered wood product called ProdEX, made by Prodema. It’s natural wood with a protective outer film of PVDF, so it doesn’t require any maintenance. I had my supplier cut down the standard 4-by-8 sheets and rearrange them in a sort of ashlar pattern. The material is very similar in color and character to Douglas fir.

DI: Did you find SIPs relatively easy to work with?

TILLS: I designed the house and gave the drawings to Tim, and he had ACH adapt them to work with SIPs. I didn’t feel like there was any compromise at all; I felt very free to do whatever I wanted.

DI: Aside from the SIPs, what other features make the home energy efficient?

TILLS: The floors and our domestic hot water are heated by a single, ultra-high-efficiency boiler. The unit also has a hot-water loop for our forced-air system.

Originally the home was designed around an underground geothermal heat pump, but that was value-engineered out when we had to make a few reductions.

Triple-pane windows help shield the home from high winds and frigid temperatures during a Wisconsin winter, and keep the heat outside when the temperature soars. Photo: Matthew Tills

DI: What are the key features of the floor plan?

TILLS: It’s a very open plan. The living room and media room step down 18 inches and there’s a low dividing wall between them. This provides visual separation but still keeps them connected with the rest of the house.

We utilized every square inch. I don’t feel like we’re heating any wasted space.

DI: Tim, you’ve been using SIPs for years. What do you like about them?

WOOD: All the insulation is built right into the panels, so I don’t have problems with wall cavities anymore. A wall framed with SIPs is actually stronger than a 2-by-6, 16-inch-on-center framed wall. And you can make a house airtight very easily with SIPs.

DI: Mary, can you expand on the benefits of using SIPs in residential construction?

BURK: With stick framing you have gaps between the studs, and that’s where air is typically lost. You don’t have that air infiltration with SIPs because the entire panel is made of foam with laminated wood on each side.

R-values will vary depending on the thickness of the walls, but the thing that makes SIPs the most functional structural system is that they create a completely airtight building envelope. As a result, the HVAC system can be downsized.

SIPs fabricated by ACH Foam Technologies at its Fond du Lac, Wisc., plant make the structure sturdy with virtually no air infiltration. Photo: Matthew Tills

Once we get the architect’s drawings, we fabricate the panels exactly to those specs, so they install quite a bit faster than traditional stick framing.

In the case of Matt’s house, the roof panels had to be thicker to withstand heavy snow loads. We’ve also documented cases where SIPs stood up to hurricane-force winds and tornadoes. They’re very strong.