A First Job's Leadership Lessons With Real Staying Power

U.S. Steel South Works began as the Chicago Rolling Mill Company in 1882, and it continued nonstop, under several names—Carnegie Steel, Illinois Steel, U.S. Steel, and finally USX Corp.—for more than 100 years until closing in 1992. A mammoth, powerful beast fed by immense quantities of water, natural gas, diesel fuel, and electricity—along with the backs and brains of thousands of workers on each shift—running the mill demanded constant vigilance. Anything less, and serious injury or death rose from merely possible to probable.

A key element in the American “Arsenal of Democracy,” which turned World War II in our favor, the South Works Structural Mill became the largest of its kind on the planet. From the front-end “soaking pits” where 20-ton stripped ingots were brought to more than 2,000° F for rolling, to the far reaches of the finishing end where steel beams were loaded into rail cars, it would have stretched more than a mile laid end to end. South Works steel went into most of the skyscrapers in North America, America’s largest aircraft carriers, destroyers, and submarines, and on down to countless interstate highway overpasses and the miles of piling bar that hold back lakes and oceans. It was a heady place to start my first “career job” right out of college, still short of my 22nd birthday.

After the “circuit course” where college recruits spent a week in each of 15 mill locations interspersed with days of training off-site, we received our assignments. I was named a Turn Foreman in Structural Finishing over a crew of 70 people. Hardly any of my charges “looked like me,” with a broad array of ethnicities and countries of origin. The average age was mid-40s and I was younger than all but two or three. Several old-timers with more than 40 years of service could recount stories of the union-busting days of the 1930s when unspeakable atrocities were carried out on the workers by hired company thugs.

There were nice guys, tough guys, and two or three women on the typical crew who knew how to take care of their jobs and themselves. Perhaps the most interesting crew member represented something totally new to me. Tina, a 40-something woman, ran the kiosk generating punch cards that determined the fate of a 10-ton steel beam as it moved through the back end of the mill. Tina had platinum blonde hair, tons of makeup, the tightest onesie work suit ever, and was extremely flirtatious. Today’s 22-year-olds would hardly be phased by a Tina, who up until the previous year had always been known as “LeRoy,” and on the company roster was listed as male. It was a different era and I was naïve, but the crew helped me figure it all out.

One might guess life wasn’t easy in a steel mill for Tina so many years ago, but you’d be wrong. Tina was great at her job, took care of business, and managed the ever-critical “steel lineup”—the steel mill equivalent of a construction schedule—to a T. Nobody messed with Tina, and therein was my first big “people” lesson: When there’s work to be done, if someone proves their worth, most accept them for who they are and couldn’t care less about what they wear or their personal relationships. And if someone is part of your tribe, despite any internal squabbles, you protect them from any outside threat.

Thanks for the Management Advice, Dad

I remember calling my dad the day after my first shift as a turn foreman. I described the impossible task of leading 70 people, most of whom could be my parent, in a mill I knew absolutely nothing about. He offered advice that saved me. “Help them. Offer to bust your can to do whatever they need to make their work or their lives better, whether it’s getting a tool replaced or a paycheck straightened out. Help them, and they’ll run the mill for you.” I recall it almost word for word. Then, after a long silence he added, “And don’t BS them. Ever. If you don’t know, say so, then go find out. If it’s bad news, tell them straight.” He went on to tell me this was the best learning opportunity I’d ever have and I should resolve each day to make it so. I did my best to follow his advice. And, as usual, dad was right.

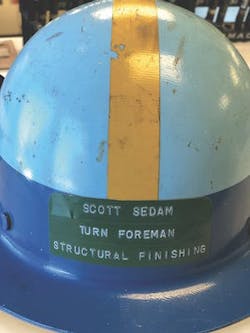

I was now an official member of management, signified by my two-tone blue hard-hat with the yellow stripe down the middle. The yellow stripe indicated Structural Division, and I wore it with pride. Workers referred to all of us as a group—the “blue hats”—and had developed an elaborate signaling system so everyone knew where we were at all times. It was an interesting management culture, to say the least. In a nutshell, this was how we were taught to think as front-line supers:

First, everyone is guilty until proven innocent. Never trust anyone except another blue hat from Structural Division—and even then, be wary. Blue hats from other mill divisions were competition, not colleagues. The “no trust” list included all yellow hats—United Steel Workers (USW) members—and especially their official representatives, called “grievance men.” Also on the no-trust roster were the white hats from engineering and the green hats worn by internal safety and anyone from OSHA or the Environmental Protection Agency.

It seems that when it comes to people, it’s never easy, and most of the learning will be on the job, while you make every mistake in the book.

It was hard not to become cynical and, in truth, most people did—on both sides. Our mill general superintendent, the top guy, was named “Swede Savage,” a befitting appellation. Our department manager was named “The Colonel,” after his stint as a Marine Corps officer, and he spent his career trying to establish Marine Corps discipline within the ranks of structural finishing and the USW.

After several months working the day shift in this culture, my idealistic notions about the world were severely challenged. Then something serendipitous occurred. I moved to live up near Wrigley Field on Chicago’s north side. The commute up and down Lake Shore Drive back then was reasonable, and up north was a much better place to be for a young buck in the city. I quickly discovered there is no better place on Earth for a 22-year-old than whiling away summer afternoons in the Wrigley Field bleachers drinking Old Style beer and making friends with the locals. This discovery inspired a change in my work schedule and set me on a different course regarding people.

In the mill, we worked rotating shifts: 7 a.m. to 3 p.m., 3 p.m. to 11 p.m., and 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. But no one, especially the older guys with families, wanted to work 11-7. This became my opportunity. I had reached the point where I was trusted on the night shift, and volunteered to work as many nights as possible so I could spend as many afternoons as possible at Wrigley. Who needs sleep when you’re 22?

Working Nights and Days Turns Out to Be Night and Day

After a few weeks working nights, I encountered a strange phenomenon. Many of the employees who were marginal or even lousy workers on the day shift were just fine on the night shift. It wasn’t because I had a breakthrough in management skills, but everything seemed easier on the night shift. Work was, dare I say, fun.

Then September came, the Cubs (as always) were out of the playoffs, and it was time to go back to the regular swing-shift rotation. And it’s there the real shock hit me. All of these great people on the night shift turned right back into marginally performing automatons when working days! What was going on?

Here’s what: On the night shift, a millwright would help an electrician, and a pipe fitter would help a rigger. On the day shift, it was always “not-my-job.” On the night shift, the union rep always looked the other way on minor work rules and let you put the right guy in the right job to make things work. On the day shift, USW work rules ruled. Ten times more grievances were filed against supervisors on the day shift compared with the night shift. On nights, people truly looked out for one another. They shared their food, their problems, their lives. On days, people ate alone or in small groups and talked about work only, mostly how bad management was. It was every man for himself.

They were perfectly capable of being good workers—or poor workers—depending on their environment.

I started following the performance statistics. Production was higher on the night shift, quality was better, and the accident rate was lower. Go figure. Of course, management thought we were just cheating on the night shift. But something profound and important was taking place and the controlling variable could not be the workers. They were perfectly capable of being good workers—or poor workers—depending on their environment. I began to realize everything the senior managers taught us about the workers was wrong. Because middle management and above worked only day shifts, they never saw the other side of these people. Their workers were smart, capable, caring, conscientious—when they chose to be. Or was it when they were allowed to be?

Discovering What Motivates People to Be More Engaged Employees

So, what was the variable? For just the finishing end of the day shift, we had one division superintendent, three department superintendents, four general foremen, two assistant general foremen, nine turn foremen, plant engineering, corporate engineering, OSHA, EPA, five or 10 union reps, safety coordinators, a host of people from quality control—and 150 people working. On the night shift, we had three foremen, one QC inspector—and 150 people working. Management theorists might call this “a clue.” It took a while, but I got it, and this knowledge changed the way I look at the world, forever. Rather than give you all of my conclusions from this episode here, I suggest you share this scenario with your team and talk about the implications and draw whatever parallels you can to home building. Consider, however, these questions:

Is it possible some of our trades and even our own employees we consider poor performers are simply responding naturally to the environment management has created? Is it possible those same people could become valued team members if we treated them differently? Is it possible they are great trades for some other builder who has cracked the code on this thing? Could the real problem be us, not them? Have you ever fired someone, only to see them do well with another builder, or vice versa? I know you have. Ask yourself why.

Eventually I saw the writing on the wall, as we cut back from around 12,000 employees when I arrived to fewer than 8,000, with maintenance and new investment in the mill a fraction of what it had been. I returned to college for an MBA. Course after course in accounting, finance, statistics, marketing, management, and a couple on human resources—which were almost totally on law, rules, regulations, and policy. Even the management classes were taught on a level that was more strategic than tactical. I found the models helpful, such as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and Herzberg’s motivation-hygiene theory. Yet I don’t recall one instance where we applied these theories to a real-life work problem. So, even in a well-regarded MBA program, very little was taught or discussed about the day-to-day ins and outs of how to work with people.

How and where do we learn about people? What motivates them? What gives them hope, makes them feel accomplished, drives them to get out of bed and come to work? How do you build trust? How do you breed loyalty? What moves them to do their very best job with what they’ve got, or not? Ask senior managers about the toughest problems they have dealt with in their careers and more than 90% will look back on “people problems.” It seems that when it comes to people, it’s never easy, and most of the learning will be on the job, while you make every mistake in the book. Meanwhile, my dad would tell you, first, be of help. Every day is an opportunity. Make each one count.

I remain an ardent disciple of quality guru Dr. W. Edwards Deming, nearly 30 years after his passing, who said, “There is no substitute for knowledge.” I have found this to be true, with one caveat: Knowledge doesn’t accomplish much if it’s not applied to solving and preventing problems on a continual basis. If you’re really lucky, you had a job early in your career that taught you a lot of the truths—and debunked many of the myths—regarding people, adding to your store of knowledge. Such an experience can help you avoid the worst mistakes. How fortunate for me it was my first job out of college.

Access a PDF of this article in Pro Builder's April 2020 digital edition