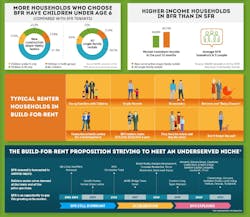

The build-for-rent (BFR) market continues to gain steam: Builders constructed 60,000 homes for rent last year, with potentially 80,000 more this year, according to housing economist Brad Hunter. An estimated $10 billion will be invested in the BFR market in 2021, Hunter predicts.

In May, the Housing Innovation Alliance (HIA) convened a panel of five industry experts to gather their insights on BFR and its potential for innovation.

“There’s so much interest in build-for-rent right now, it’s a great opportunity to think about making housing more efficient, affordable, and attainable,” said the moderator, Margaret Whelan, an HIA board member and the founder-CEO of Whelan Advisory, a New York-based boutique investment bank that advises housing and construction companies.

A few key takeaways:

Build-for-rent housing is on an upward trajectory—that will keep going up.

The BFR market has evolved quickly from a decade ago—“when it was just a dream,” said Richard Rodriguez, executive vice president of Amherst Residential, a BFR leader. At that time, BFR mostly involved turning builders’ leftover single-family housing stock into rentals. Today, developments and units are getting built specifically as BFR.

“They looked at me like I had three heads,” Rodriguez recalled of his early BFR conversations with construction company leaders. “Now, it’s a larger and larger part of their business.”

Rodriguez estimated that, five years from now, 20 percent of all new housing units in the US will be BFR.

RELATED: 5 Ways To Make Distinctive Build-to-Rent Housing Units

The market has been particularly strong in Phoenix, which Whelan called the birthplace of BFR: After the Great Recession, the city had plenty of empty new homes that became rentals.

According to the panelists, BFR appeals both to younger people who don’t want to take on the risks of homeownership and to older people who need or simply prefer to have others take care of home maintenance.

For developers, BFR promises long-term revenue over 15 to 25 years—as compared to the one-time returns on single-family homes, Rodriguez said. That longer timeframe means developers can invest and innovate more upfront, knowing they have more time to realize their ROI.

Building BFR means building more efficiently.

BFR’s more standardized construction products and processes lead to more predictable planning and scheduling and overall greater efficiency, the panelists have found.

Prefab BFR allows manufacturers like Truss Fab to “push units out faster and with fewer mistakes in the field,” said Dean Rana, president of Truss Fab Companies, an Arizona-based truss manufacturer.

And a more standard, repetitive process requires less skilled labor, which is no small benefit in a tight labor market. “That’s been probably the best benefit for us in entering the BFR market—that dependability and reliability of labor,” Rana said. “We’re doing double the volume with the manpower we have because of the simplicity of BFR.”

BFR’s simplified process and product also lead to time savings. “Cycle times are definitely improving with essentially the elimination of optionality,” said Steve Baum, executive vice president of construction at Brewer Companies, a Phoenix-based plumbing contractor.

In recent years, Brewer Companies set up its own training academy, with a focus on BFR. According to Baum, the BFR trainees have shown much better progression learning BFR’s more limited options, compared to the trainees who have to learn many more options available in the single-family sales market.

“It makes the crews more efficient, it increases our quality, and our cost and rework go down,” Baum said.

The insurance industry has taken notice: “Cycle times are shorter, builds are happening faster and more efficiently, and the losses seem to be fewer and farther between as a result,” said Matt Nicholas, vice president of Alliant Insurance Services, where he focuses on real estate and construction.

That efficiency can lead to bigger margins. “If you look at the gross margin or return on capital for the 20 or so publicly traded homebuilders, it’s the folks that have the simplest product that tend to have the highest margins and returns,” Whelan said.

A streamlined product benefits consumers, too. “The bottom line is we need units. No one cares about the extended garage—they just need space to live,” Rana said.

Build for tenants, not owners.

BFR developers must address a perennial landlord question: Should they try to keep tenants as long as possible to avoid costly turnover, or should they seek shorter-term residents so they have the opportunity to increase rent with each turnover?

“I think the answer is probably in between,” Rodriguez said. “You want good residents, and you build price increases into the lease itself.”

Another question for BFR builders: Do their tenants want smart tech? While Rodriguez said one-third of Amherst’s BFR homes have basic smart tech, like temperature control, he hasn’t seen a correlation between how long tenants stay and how well the unit is constructed—assuming a baseline of good construction. “Beyond the walls, I’m not sure the resident cares,” he said.

But builders should think about the durability of materials, Rodriguez said. Baum agreed: “Select the right fixtures and finishes that will be longer lasting. Don’t go cheap with fixtures,” Baum said.

Garbage disposals, faucets, countertops—BFR tenants will be harder on these components, and on the units in general, than single-family homeowners who have a vested interest in the property.