The 2023 State of Supply Chains

In Tony Matter’s first year as marketing director for M/I Windows and Doors, in 2014, guaranteed lead time for product delivery was one week. To Matter’s recollection, that had been the case since at least the early 2000s. It remained that case for years after his hiring.

“Windows were showing up to suppliers like that all day, every day for more than 15 years,” says Matter, who now serves as vice president of creative and brand for M/I Windows and Doors. “That is,” he says, “until the pandemic.”

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization officially declared COVID-19 a pandemic. At the time, 118,000 cases and 4,291 deaths had been documented across 114 countries. Eight days later, California issued the country’s first statewide quarantine order. Four days after that, nine states had implemented similar stay-at-home orders. Within a week, it was 20 states. By mid-April, 42 states were on lockdown.

The pandemic was a fog over everything, disrupting everything. Supply chains, especially for building materials, were an early victim of the chaos.

“We were normally talking delivery in four to six weeks,” says Dan Butterfield, vice president of residential sales for flooring manufacturer Dal-Tile, a division of Mohawk Industries. “COVID tripled or quadrupled that.”

In 2020, global manufacturing output fell by more than 15%, the steepest drop since 2008, and delivery times plummeted to 20-plus-year lows.

At M/I Windows and Doors, where “one week lead time” had been a mantra for over 15 years, delivery times were now being tracked in months. “At the height of the pandemic,” Matter says, “lead times were up to 30 weeks, around six months, for some product lines; and no products were being shipped in less than 10 to 12 weeks.”

At the time, these disruptions—to production, logistics, etc—were described as simply problems of the pandemic. Three years later, hindsight reveals a more complicated reality.

STORY SECTIONSResidential Construction Experiences Supply Chain ProblemsPandemic’s Over But Its Problems RemainThe Roots of Supply Chain DisruptionsThe Outlook on Supply Chains

Residential Construction Experiences Supply Chain Problems

“March 2020 hits and it’s like the sky is falling. No one knew what was going to happen with COVID,” recalls Kevin Wilson, who heads strategic sourcing and sustainability for national builder Tri Pointe Homes, which in 2022 delivered over 6,000 new homes.

As manufacturing was an early victim of disruption, so was residential construction. On the same day California issued the country’s first stay-at-home order, the National Association of Home Builders warned its membership to expect delays, recommending their contracts reflect as much. That same month, Atlanta ceased accepting new construction permits, Miami stopped inspections, and multiple cities and states halted most residential construction altogether.

Bottlenecks formed quickly in the chaos, and by April, housing starts were reportedly down 22%.

Contractors faced plenty of problems in those early months. Home builders reported increased cancellations and problems generating new client traffic as well as convincing staff and trade partners to report to construction sites, according to the National Association of Home Builders—similar to the problems reported by remodelers. But as 2020 went on, one problem persisted and escalated from a problem to the problem: supply chains.

“All of a sudden we were seeing impacts on lead times that were delaying projects and impacting people’s ability to move into their homes or finish their projects,” says Ryan McDaniel, partner and director of design at Brandon Architects, a custom build firm out of Costa Mesa, Calif.

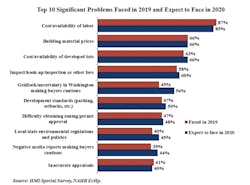

Whereas in December 2019, material availability was not a serious concern for builders, by the end of 2020, it was a chief concern.

While material prices have long been a concern for residential construction professionals, availability of those materials is a recent problem unique to the pandemic and post-pandemic eras.

Image: NAHB

“We were scrambling,” Wilson admits. “And it wasn’t just cabinets and windows. It was garage doors and appliances and flooring. It was electronic door locks, light fixtures, ductwork, HVAC systems.”

At the same time, problems with material pricing were being reported nearly unanimously. It was the first time in five years that the “price (and) availability of labor” wasn’t membership’s top concern.

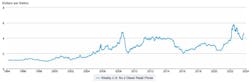

The cost of framing lumber jumped 250% in three months and structural panel prices spiked 300%. Softwood lumber prices more than doubled from April to September 2020. By 2021, prices of plastics and PVC products had nearly tripled and OSB prices had risen 510%, among myriad other instances of increases. Fluctuations were felt across product categories, dramatically quickening the annual pace of rising home costs. The $150,000-plus rise in median home price from Q2 2020 to Q4 2022 was its steepest climb in history.

In the history of recorded US home prices, there has been no steeper rise in the median price of homes than in the period between Q2 2020 and Q4 2022.

Image: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED)

While new problems arose and existing ones evolved over the course of the pandemic, and even into today, the price and ready availability of building materials, despite their varying degrees, have remained a constant worry, registering as the top concerns for builders in both 2021 and 2022. In fact, the health of supply chains at-large has and remains a global concern. A survey conducted by CNBC revealed that more than half of “logistics managers at major companies and trade groups” don’t expect supply chains to return to normal until 2024 or after. Twelve percent don’t expect it to ever return to normal.

Pandemic’s Over But Its Problems Remain

On May 11, 2023, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention declared that the COVID-19 outbreak was no longer a Public Health Emergency. After more than three years and nearly 7 million reported deaths, the CDC’s announcement marked the beginning of the third era of modern history, from pre-pandemic to pandemic, to now post-pademic. But while our state of emergency has lapsed, its impacts linger.

“A year ago things were absolutely worse,” says David Logan, a senior economist and director of tax and trade policy analysis for the National Association of Home Builders, who’s been closely monitoring the health of building material and product supply chains. “Whether domestic or international, generally speaking, supply chains are again functioning. But absolutely there are still disruptions.”

In residential construction, the general tenor is cautiously optimistic.

“We’re hearing some of our dealers report that supply chains are better, but there is an acknowledgement that demand is down,” says John Burns Research and Consulting’s (JBREC’s) Director of Building Products Research Chris Beard. “That may play into why materials are more available. Manufacturers are getting caught up on their backlogs.”

On both the manufacturing and contractor sides, regardless of the nuance, there are at least acknowledgements of improvement.

“I would just say, coming into 2023, we’re seeing the light at the end of the tunnel,” Dal-Tile’s Butterfield remarks.

At Tri Pointe Homes—which cut its backlog in half from 3,000-plus in 2021 to just under 1,500 in 2022—Wilson says that the “industry is healing very well from the pandemic.” But adds, “We’re still seeing disruptions kind of product by product.”

Product Categories Still Facing Disruption

Across the industry, despite improvements in lead times and availability, there are lingering reports of building product supply chain disruptions—which are, in some cases, admittedly more anecdotal than rooted in readily available data. As a supplement to our "2023 State of Supply Chains," we've collected a number of those reports... READ MORE

The Roots of Supply Chain Disruptions

Still, one of the benefits of having moved past the pandemic era, regardless of its lingering effects, is hindsight. We can examine where things went wrong the worst, and admittedly the worst includes supply chains—which suffered myriad, often interconnected problems both stemming from and transcending the pandemic. Among the most prevalent problems were uncertainty, the availability of raw materials, diminished or changed production capabilities, inclement weather, the ability to dependably and affordably ship product, and labor.

Uncertainty

Perhaps the most obvious of those problems that plagued manufacturers and contractors alike during and certainly at the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak was uncertainty.

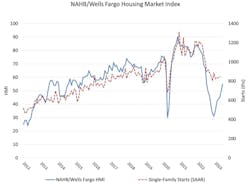

Builder confidence plummeted during the first month of the pandemic, according to the NAHB/Wells Fargo Housing Market Index. On a scale of zero to 100—where zero’s “poor,” 100’s “good,” and 50’s “fair”—builder confidence fell from above 70, where it had been for six consecutive months, to 30. It was the most dramatic drop in builder confidence ever recorded through the index, which dates back to 1985.

After builder confidence plummeted in the early months of the pandemic, it quickly rebounded alongside home starts. However, the industry has struggled to maintain its optimism, with confidence again falling steeply in 2022.

Image: NAHB

Throughout that first year, “almost 100,000 businesses had to be temporarily closed” and “over 65,000 businesses (had to) permanently close,” according to a 2020 paper published in the journal Industrial Marketing Management and later cataloged in the National Library of Medicine.

“Everybody hit the brakes—not just us but manufacturers, as well,” explains Wilson. “Manufacturers said, ‘we’re not gonna build inventory.’ They didn’t know where it was going to go. They didn’t want to house it. They didn’t want it sitting on shelves.”

It’s a fact manufacturers won’t shy away from.

“In March 2020, we had no idea what was going to happen on the residential side,” says Steve Proctor, director of sales and marketing for True Residential, a luxury refrigerator manufacturer.

“Right from the onset there was an immediate shut down, or at least a shut down of most things,” says Matter, clarifying that neither M/I Windows and Doors nor its parent company MITER Brands ever fully closed during the pandemic. “That was an instant challenge, and continued to be so even after things reopened.”

Dal-Tile’s Butterfield recalls, “There was just uncertainty. We’d have people just not show up, and therefore factories were not producing product. So you had these variables on the manufacturing side of it. The question was: when is the product that we need going to be produced?”

Wilson describes the initial response from manufacturers, at least from the contractor’s perspective, as the result of a system working too long untested. “When a system’s working for decades, you don’t really know about it. You don’t know how to fix it because you don’t really know how it broke,” he explains. “That was a challenge for a lot of our manufacturers.”

Raw Materials Shortages

A more tangible problem was the shortages that manufacturers themselves were, and in some cases still are, experiencing.

“The entire supply chain was disrupted,” says Dave Rumbaugh, vice president of logistics and specialty purchasing for 84 Lumber, which still managed $4 billion in sales in 2020. “This included all materials, equipment to manufacture finished goods, and equipment to build and transport product.”

By the end of 2020, raw materials specifically were proving a signifcant hurdle for manufacturers, as nearly half of the National Association of Manufacturers’ (NAM’s) membership was describing rising raw material prices as a “primary current business challenge.” By Q4 2021, it was the top concern, followed by “supply chain challenges.”

The global price of tin, a historically expensive material often used in material manufacturing as a coating for other metal materials, nearly tripled between April 2020 and March 2022, when it reached an all-time high of approximately $44,000 per metric ton.

Image: FRED

“Anything that we were buying from other suppliers became pretty difficult to get a hold of,” Matter says.

As the pandemic ensued, prices for raw materials spiked as supply chains choked. Several commodities crucial to building product manufacturing saw prices reach 20-year highs, including aluminum, iron ore, tin, metals in general, natural gas, and softwood.

The global price of aluminum, a material with myriad applications in building material manufacturing, often used for window and door frames, a variety of HVAC systems and components, solar panels, cladding, and more, rose by more than $1,000 per metric ton between 2020 and 2022.

Image: FRED

“We source a lot of aluminum, and we were seeing a big impact on cost,” True Residential’s Proctor explains. “We typically lock in contract pricing from our suppliers and we’re good for a year and will negotiate a few points when we renew. But price changes were coming in almost weekly. Suppliers would say, ‘If you want the metal, this is the price.’”

Shortages of a certain high-grade of steel, in fact, continue to be a primary factor in the current distribution transformer shortage, for which lead times since 2020 have risen 400% to around 12 months. “There seems to be only a handful of companies that produce this type of steel,” JBREC’s Building Products Research Director Bread explains.

During a meeting with the Department of Energy on the subject of transformer shortages, representatives from Powersmiths Inc, a transformer manufacturer, described how limited availability of certain steels have hindered the company’s ability to produce. A record of the meeting reads:

Powersmiths commented that many of the high performing grades are only available from overseas suppliers and recent shipping and port access challenges have increased market uncertainty and availability to those grades…

Powersmiths commented they are currently experiencing diminished availability of several grades of steel and increased costs as steel suppliers are shifting to serving the EV market without plans to bring transformer-grade steel capacity back.

Certain derivative materials and components crucial to manufacturing also faced significant disruption. Durable plastics like PVC—used in pipes, fittings, flooring, wall coverings, window frames and vinyl siding—and polypropylene—used in carpet and for the linings in refrigerators and washing machines—experienced huge price jumps in 2021, in some cases rising by more than 300%. Semiconductors, too, used in factories and appliances, have and still suffer from shortages that have reportedly cost the industry more than $500 billion in revenue.

After their steep climb during the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic, global commodity prices are trending down and, according to the World Bank, are expected to continue doing so into 2024.

Image: FRED

“In our world of appliances, there’s electronics, there’s safety things you have to vet,” Proctor says. “It’s not like finding a new lumber supplier. It’s quite the process.”

And while there have been relative improvements on the raw materials front (ie, commodity prices are trending down and plastics prices have returned to pre-pandemic level) more than half of NAM’s 14,000 members continue to cite raw material prices as a primary challenge.

Product Allocations and Consolidation

The early problems of the pandemic stunted manufacturing. A 2020 report from the Institute for Supply Management described it as “a level of manufacturing-sector contraction not seen since April 2009, with a strongly negative trajectory.” Meanwhile, demand for new homes and remodeling rose.

“We were extending lead times because the orders were outpacing what we could produce,” MITER Brands’s Matter admits.

“When we started seeing the drop on the commercial side, we were waiting for what was going to happen on the residential side, thinking it would be more of the same,” True Residential’s Proctor recalls. “I think it was in about May (2020) when we started seeing residential orders coming in at a higher rate than what was typical. And at the height of the pandemic, demand really outweighed our supply.”

Freddie Miller, vice president of supply chain for ProVia, a manufacturer of a wide array of products including doors, windows, siding, and roofing, recalls the difficulty of meeting that building demand. “With the backlog we accumulated because of supply challenges, we couldn’t produce everything that was required or on order in time.”

As manufacturing orders were reaching record highs in 2021, so were backlogs. The imbalance of production capacity to consumer demand forced manufacturers to make tough decisions. “‘Allocation’ became a very popular word,” Dal-Tile’s Butterfield admits.

In manufacturing, “allocation” refers to the process of intentionally limiting the availability of SKUs, or stock keeping units, to buyers based on a predetermined criteria.

“We had a lot of builders and developers come to us, knowing our capacity. We really felt like we needed to be sensitive to that, but protect those who brought us to the dance,” Butterfield says. “So when I talk about allocation, it really was making sure that we fed those who were in a program with us. And of course, if there was an opportunity, with any sort of coverage, to help others out, regardless of agreements, we certainly did so.”

While not widely reported, allocations seem to have impacted materials throughout the supply chain.

“The practice has been particularly prevalent for roofing and siding,” JBREC researcher Beard says. “Manufacturers just couldn’t produce enough.”

Builder Rob Myers recalls issues with concrete, as well. “As of last fall, ready-mix concrete was on allocation,” he says. “Producers weren’t able to get enough cement and so everybody that was ordering it was on allocation.”

There were also instances of allocations for appliances. “We make our own clear ice machines and we had customers trying to buy 50 or 100 at a time,” Proctor says. “We’d say, ‘we can’t do that.’ We had to make sure we had enough supply for the market. So any orders more than 10, or something like that, we’d flag it.”

Backlogs and persisting demand sent manufacturers scrambling to find ways to increase capacity.

“What we’ve heard from manufacturers is that there’s been optimization of SKUs,” Beard explains. “For roofing, for instance, there was considerable streamlining of shingle types and colors, keeping the more popular ones.”

Optimization is also how MITER Brands increased production, according to Matter. “We opened up our manufacturing capacity by streamlining our product offerings,” he explains. “Certain paint colors and laminate color options were reduced during the worst of it.”

For some manufacturers, optimization meant reducing catalogs by hundreds of options. “It was SKU consolidation, narrow and deep,” Butterfield explains. “If we had 1400 options in a certain space—let’s say, mosaics from China—we went down to 40.”

And while that consolidation did limit options, it also increased availability of more popular products—which some builders applauded.

“We were absolutely proponents of limited SKUs to increase production,” Kevin Wilson of Tri Pointe Homes admits. “If a manufacturer could promise delivery on ‘x’ many of whatever product, we would agree to curate choice in our design studios accordingly. I think that was a really good exercise in discipline for builders.”

As of 2023, orders and backlogs for manufacturing at-large have dipped below even pre-pandemic levels.

Inclement Weather

One unavoidable issue that compounded the problems of shipping and production during the pandemic, and in some cases created them, was the weather, particularly in the Gulf Coast.

“The severe weather that hit Texas and Louisiana in February 2021, had such a huge impact on manufacturing output for the petrochemical industry,” Logan, NAHB’s senior economist, says, referring to Winter Storm Uri, the most costly winter storm ever recorded. “Texas is such a critical region for the manufacturing of those components. For about a week or two, that entire industry was offline and all of a sudden you had zero output.”

Several storms hit the Gulf Coast throughout the pandemic, including Uri as well as Hurricane Ian—the third costliest storm in US History—challenging supply chains.

Two of the 10 most costly weather/climate disasters in history—Hurricane Ian and Hurricane Ida—happened during the pandemic.

Image: National Centers for Environmental Information

“A lot of materials come from the Gulf Coast. And so on top of the pandemic, you had weather-related issues, as well,” Miller of ProVia says. “It’s still impacting us on the siding side.”

It’s a problem still impacting the availability of transformers, as well. “Any time we have a natural disaster,” Logan explains, “all the transformers that you see explode from lightning strikes and what have you, those are the transformers that get replaced first.”

During Hurricane Ida in August 2021, nearly 6,000 transformers were either damaged or destroyed. According to Entergy, which provides electricity to more than 3 million homes throughout the Gulf region, “the number of (telephone) poles damaged or destroyed during Ida (was) more than hurricanes Katrina, Ike, Delta, and Zeta combined.”

Joy Ditto, president and CEO of the APPA, published an op-ed in November 2022 saying that a supply chain shortage coupled with Hurricane Ian had, at least in Florida, "depleted the equipment reserves of many utilities that lack adequate distribution transformers and other necessary grid equipment." She added, "It is unclear if we have the transformers to rebuild after another significant weather event this year—a situation that is untenable for a country that requires electricity for everything we do."

For 2023, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is, with 70% confidence, predicting a “near normal” hurricane season, which may include upwards of nine hurricanes and four “major” hurricanes.

International Shipping

Central to many of the supply chain disruptions during the pandemic were the problems affecting the physical shipping of product.

“Transportation was a big issue, and continues to be so,” Beard, JBREC’s Director of Building Products Research, says. “There was a lot of commentary about ocean freight in particular.”

All methods of international transport were impacted by the COVID-19 outbreak. Air shipping, for instance, nose dived in the early months of the pandemic, with cargo availability dropping nearly 30% year over year by April 2020—mostly due to canceled flights, according to a report from the US International Trade Commission. Air transport did ultimately rebound, posting consecutive months of improvement by mid-year 2021, and cargo capacity has since returned to pre-pandemic levels, but, according to international shipping platform Freightos, prices remain “exceptionally high.” Still, it was disruption in maritime shipping—which accounts for 80% of international trade—that appears to have most significantly impacted the global supply chain.

“There was a lot of uncertainty in a lot of foreign markets, especially China,” Butterfield, head of residential sales for Dal-Tile, recalls. “We didn’t know when we were gonna get material. We didn’t know when we were going to get a (ocean freight shipping) container. We didn’t know what that container was going to cost.”

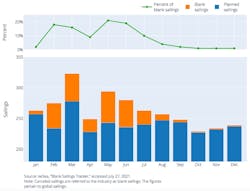

The pandemic’s impact on ocean freight was initially minimal, as container prices remained relatively consistent for the first half of 2020. But in June, after more than 1,000 scheduled sailings had been canceled in anticipation of falling demand, prices for shipping containers skyrocketed, breaking a decade-long trend of price stability. In 12 months, as demand for imports unexpectedly increased, prices rose over 300%, from about $1,500 per container to just over $6,200. By September 2021, manufacturers (and all shippers) were paying $11,100 for a single container.

The increase in blank sailings as a result of anticipated low demand led to a shortage capacity that shipping companies initially struggled to come back from, according to a report from the US International Trade Commission.

Image: US International Trade Commission

Accounting for even a single, small shipping vessel, which can carry 12,000 to 14,000 containers, the increase in cost would have amounted to roughly $100 million in additional, at-large spending for international shipping. There are over 50,000 vessels in the global merchant fleet, and the world’s largest cargo ships can carry upwards of 24,000 containers.

“Container costs skyrocketed for manufacturers trying to get parts and pieces to build on-shore as well as those doing whole-scale production in China or overseas somewhere,” remembers Wilson, Tri Pointe Homes’s head of strategic sourcing.

As the pandemic continued, imports from Asia rose, hitting record levels in 2022, contributing to extreme congestion at US ports. According to data from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), half of the world’s merchant fleet is owned by Asian companies.

“Anything imported suffered just because we couldn’t get containers across the ocean without them getting stuck at ports,” Wilson explains.

“I remember stories of boats sitting at the ports for days, weeks, even months at time,” Matter of MITER Brands recalls. “They just couldn’t get them in there.”

This image, taken in October 2021, shows just a fraction of the freighter congestion (ie, the white specks) that had built outside the Los Angeles and Long Beach ports in California.

Image: NASA Earth Observatory, Joshua Stevens

At the neighboring ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, for example, two of the busiest ports in the US, prior to the pandemic it was typical to have, at most, one ship anchored outside of the ports at any given time, according to the Marine Exchange of Southern California. The record for container ships anchored outside of the port at any one time was 28, set in 2014. Starting in August 2020, that record was broken near daily for more than a month. At one point, more than 100 container ships were “backed up,” attempting to access the ports. It set a new standard for what was to be “typical” congestion at the ports—and really all ports—until well into 2022.

As of Q2 2023, port congestion had “improved significantly from its peak in Q4 2021, but it is still far from normal,” according to shipping software provider Go Comet’s quarterly port congestion analysis, and container prices, which remained elevated throughout 2022, have returned to pre-pandemic levels. Today, labor availability is the biggest hurdle to importing goods into the US. As recent as June 2023, multiple major ports in the country were being forced to near close as a result of worker shortages.

Domestic Shipping

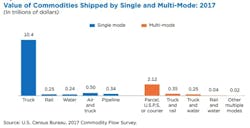

Problems transporting materials and products during the pandemic were not limited to international supply lines but impacted domestic shipping, as well. Rail freight activity, for instance, dropped 15% in the early months of the pandemic; though, activity quickly rebounded—a response, at least in part, to “capacity constraints in the trucking market.” More than 70% of the goods shipped within the US are transported via truck.

Plagued by persistent, widespread employee shortages that preceded the COVID-19 outbreak, the trucking industry was quickly strained by the pandemic, leading to steep drops in driver availability and cargo capacity. And while capacity momentarily rebounded at the tailend of 2020, it again fell in 2021 and continued to do so throughout the year, into 2022, and now into 2023, according to freight forecaster ACT Research.

According to the US Census Bureau, "trucks transported ... $10.4 trillion of the $14.5 trillion of the value of all goods shipped in the United States in 2017, the latest year for which statistics are available."

Image: US Census Bureau

Trucking cost per mile and cost per hour, in large part to spiking diesel prices and limited driver availability, hit consecutive record highs in both 2021 and 2022, with 2023 data pending. This led to an increase in trucking companies refusing service on rates contracted in advance (ie, asking for more money).

“We would get to Christmas, and we’d have this domestic shipping company locked in at a certain rate, and all of a sudden a large company like Amazon or Wal-Mart pays them double,” Dal-Tile’s Head of Residential Sales Butterfield recalls. “All of a sudden, your shipment isn’t showing up tomorrow. We had to deal with a bit of that jockeying for priority.”

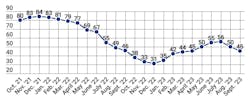

At their peak in late June 2022, US diesel prices hit an all-time high of $5.78 per gallon, more than double the $2.85 per gallon that was available in March 2020. And while prices have fallen for most of 2023, they have again began climbing in recent months. As of September 2023, diesel in the US is priced at $4.59 per gallon.

Image: US Energy Information Administration

Where the average rate of refusal for trucking companies to honor previously contracted rates was roughly 5% before the pandemic, by 2021 it had risen to nearly 30%.

Today, manufacturers continue to experience trucking freight problems, including reduced cargo capacity, gas prices that remain above pre-pandemic levels, and a driver shortage that’s projected to worsen.

”Drivers and delivery equipment are still a challenge with delivery dates extended into late 2024,” says Rumbaugh, vice president of logistics and specialty purchasing for 84 Lumber. “We believe this will continue into 2025.”

Labor

A throughline connecting and exacerbating many of the problems at the root of disrupted supply chains was, and in many cases continues to be, labor.

“Probably with every manufacturer you talk to, and suppliers too, staffing has been an issue,” says Klahsen, Pella’s senior manager of corporate supply management. “It had a significant impact.”

For manufacturing specifically—where employment had already been falling for 40 years—the pandemic’s impact was steep and severe.

“Labor was an immediate challenge,” says Matter, marketing director for MITER Brands.

Manufacturing employment in the US dropped by more than a million in the first month of the pandemic, while the number of hours worked fell at a 38-percent rate in the second quarter of 2020. The worst declines in manufacturing since World War II, according to the US Bureau Labor Statistics.

“There were times during the last couple years where labor was a challenge, and we had to work closely with our supply partners,” Klahsen of Pella says. “We’d be very upfront with them about what the needs were, what we were seeing and experiencing—just really close communication.”

Wilson of Tri Pointe Homes recalls, “We were talking to cabinet manufacturers, GE appliances and plenty of others who just said, ‘Frankly, some of our line workers can get paid more and all the covid benefits that sit on their couch versus come to work.”

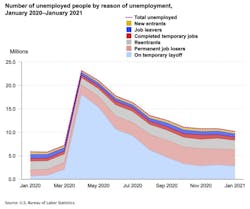

In the first month of the pandemic, while the majority of job losses were temporary, still more than 2 million were permanent.

Image: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

In April 2020, when more than 15 million workers had been temporarily laid off, the US Department of Labor released guidelines on its pandemic-triggered unemployment benefits. Those benefits saw certain eligible persons already claiming other benefits receive an additional $600 a week until July 2020, at which point benefits were reduced to $300 weekly. While the federal benefits ultimately expired September 2021, many states opted to end them early. All told, the US Government paid out $667.8 billion in pandemic-related unemployment benefits.

“That was a day-one thing that made everybody stay at home for almost an extra year,” says Rob Myers, owner of Myers Homes. “That really limited labor supply.”

The employees manufacturing lost in the first month of the pandemic weren’t recovered until May 2022, leaving the industry with backlogs it continues to work through today.

“And you can’t just pull somebody off the street and immediately inspect output,” says NAHB economist Logan. “At a plant, it can take a long time to train an unskilled worker into a skilled one. And that’s particularly true for products that require steel and aluminum.”

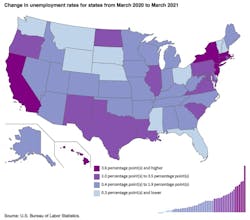

After a year in the pandemic era, unemployment rates had risen in 40 states.

Image: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Labor, though, was not a problem exclusive to manufacturers and suppliers during the pandemic. Many states, including the country’s five biggest economies—California, Texas, New York, Florida, Illinois—reached record-breaking levels of unemployment in March 2020. And while employment quickly rebounded from the extremes of that first month, problems persisted well into the pandemic. For many industries, including several that serve domestic and international supply chains, that persisting unemployment created or exacerbated worker shortages.

Trucking, for instance, has suffered from a shortage of drivers, which has reduced cargo capacities and pushed domestic shipping prices up. Worker shortages at US ports have contributed to and compounded shipping congestion and delays. As recently as June 2023, multiple major ports in the US were being forced to near close as a result of worker shortages.

“At the ports,” Matter recalls, “products just couldn’t get offloaded fast enough.”

Nationwide, there are indicators that the labor situation is improving, such as the widespread stabilization of unemployment rates at the state level. But as it specifically relates to the supply chain, the prognosis is less optimistic.

“Labor is always going to be a concern pretty much everywhere along the supply chain, to a degree,” says Butterfield of Dal-Tile.

A majority of logistics managers in a recent CNBC survey admitted that they were concerned about labor looking forward into 2024. The 300-plus respondents specifically cited employee burnout (65%), a shortage of employees with the right skills (61%), and hiring to address the skills gap (75%) as prominent problems.

The Outlook on Supply Chains

What’s clear, having left the pandemic era behind, is that there is no going back to “normal” for supply chains. There also isn’t a clear “new normal,” at least not one that’s widely applicable. There is simply adjusting to the market and world as best companies can.

“If you asked me where supply chains are today, at least from an availability standpoint, we’re about back to pre-pandemic levels,” says Freddie Miller, ProVia’s head of supply chain. “That’s probably the case across most categories.”

Pella’s senior manager of corporate supply management, Klahsen, talks about the pandemic as a catalyst for not only adjustment but positive change. “A lot of work has happened across industries and the supply chain. It’s led to a more consistent and efficient supply chain in a lot of areas,” he says.“I think that we’re just starting to experience that and will continue to do so going forward.”

And certainly there have been improvements. On a broad scale, manufacturing output is nearing pre-pandemic levels, as are times for ocean freight shipping. Employment has also improved over the past year. And according to economists and researchers at S&P Global, “supply chain pressures receded drastically in the second half of 2022”—”pressures receded” referring to falling demand—which led to fewer shipping delays.

According to global logisitcs company Flexport, in September "the TPEB increased to 59 days from 57 days, matching the fastest times since October 2020. FEWB decreased to 64 days from 65 days, inline with the average level in November 2020."

Image: Flexport

In some respects, those improvements are the result of changes made at the enterprise level. Klahsen, for instance, says that Pella has improved its risk management process, claiming, “We’re better now at reviewing known issues and identifying where the market is changing.”

Dal-Tile has been working to move production completely to North America to avoid future delays resulting from international shipping disruption. “We’re about 90% North American-made now,” Butterfield, vice president of residential sales for the flooring manufacturer, says. He goes on to add that “digital transformation is a really big part of the future,” specifically referencing the rise of virtual meetings and digital platforms built to make design meetings more productive.

Several manufacturers, in fact, have, since the pandemic began, introduced new technologies to improve their position in the market. For instance, Miller says that ProVia has found new ways of looking at internal data that allows for better tracking and forecasting. True Residential’s sales and marketing director, Proctor, says that the manufacturer has updated its website to include lead times for individual products. And according to Matter, MITER Brands is also leveraging new technologies to both better understand the market and communicate with partners.

“Through our online portal, which is viewable through a mobile app, our customers can see new lead time updates in real time,” Matter says. “We also have implemented data tools that help us make accurate projections on the market. We share quite a bit of that information with our suppliers, helping us both stay ahead of things as best we can.”

Residential construction companies have also made changes. “Builders have really stepped up,” says Ryan McDaniel, partner and director of design at Brandon Architects. “We’ve learned to prioritize and do scheduling better, and to better under the critical paths to get clients to make certain decisions, like for appliances, earlier on in the process to account for extended lead times.”

But as much as there has been improvement—as it relates to supply chain efficiency and manufacturing performance—there are certain challenges that loom large for builders and remodelers: namely, pricing.

While builder sentiment, as recorded in the NAHB/Wells Fargo Housing Market Index, has improved since the early days of the pandemic, it remains low relative to historic averages.

Image: NAHB

“Manufacturers are passing along price increases, and it puts us in a really bad spot,” says home builder Myers.

With declining housing demand brought on by rising mortgage rates and home prices as well as a persistently high (though declining) inflation rate, material prices are set to be a focal point for residential construction businesses in 2024.

“As you can imagine, everyone’s looking for the best deal right now,” Matter of MITER Brands says. “It’s not like people are complaining, but certainly everyone is asking for the best price.”

Unfortunately, even as some material prices fall, there is little expectation that prices overall will soon return (if ever) to pre-pandemic levels. “I think there’s hope for somewhat of a price decrease in the future, but I don’t know that there will be,” ProVia’s Miller admits. “I wouldn’t anticipate a lot.”

NAHB Senior Economist Logan says that while he doesn’t expect much of a fall in price, he does hope for a continuation of old trends. “Best case looking forward over the next year is that prices hold relatively stable to whatever trend they were on pre-2020.”

Prior to the pandemic, the collective price of residential construction materials had been experiencing only moderate annual increases. That trajectory, per Logan's prediction, appears to have been restablished in 2022. Still, prices overall remain at historic elevations.

Image: FRED

Some attribute the sustained increased prices to an unbalance of expenses for manufacturers. “Looking at the commodity market, you can see prices have dropped,” explains Proctor of True Residential. “But that doesn’t necessarily translate into price reductions from our supply base.”

“There were entities out there that were charging triple digit increases,” Dal-Tile’s Butterfield says of raw material and component part suppliers. “I don’t want to say they were gouging—but okay, maybe they were.”

Whatever the root cause of those higher material prices, it’s ultimately representative of the new world businesses are operating in—one that has been forever changed by the pandemic, where “normal” is a fluid word that changes the more we recover and being “adaptable” really means being adjustable. Like MITER Brands’ M/I Windows and Doors, which was forced early in the pandemic to abandon its decade-plus long trend of one-week lead times for products.

“Having competitive lead times is important, but we don’t see the need to return to one week shipping,” Matter says. “Not to say we’ll never get there, but from what we’re seeing from our customers, a two-week lead time for orders works pretty well.”