Never let it be said you can’t learn something in sixth-grade social studies — no matter what your age. My oldest daughter came home with a choice assignment: She had to write a letter to Hammurabi, a ruler of ancient Babylon and the man recognized as the first to develop a codified body of laws for governing a society. In this assignment my daughter had to explain the value of Hammurabi’s Code of Laws, written 500 years before the Ten Commandments, and put them in the context of the modern world.

I sent her to the reference stacks at the public library to research the ancient world while I did the easier part — typed in Hammurabi on the search engine Google and let it deliver the information to me. After all, I already know how to use reference books. As I clicked through the list of resources, I didn’t pay a lot of attention to the sources. That changed in a hurry when I read the following:

"For our purposes, however, there is one brief section of the Code which addresses the construction industry, covering prices of construction and contractor liability." Listed were six of the 282 laws:

228. If a builder builds a house for some one and completes it, he shall give him a fee of two shekels in money for each sar of surface.

229. If a builder builds a house for some one, and does not construct it properly, and the house which he built falls in and kills its owner, then that builder shall be put to death.

230. If it kills the son of the owner, the son of that builder shall be put to death.

231. If it kills a slave of the owner, then he shall pay slave for slave to the owner of the house.

232. If it ruins goods, he shall make compensation for all that has been ruined, and inasmuch as he did not construct properly this house which he built and it fell, he shall re-erect the house from his own means.

233. If a builder builds a house for some one, even though he has not yet completed it; if then the walls seem toppling, the builder must make the walls solid from his own means.

Where the heck am I? I wondered.

Clicking back through this link I learned that the home page was that of the Broward County, Fla., Board of Rules & Appeals — you know, the keepers of the building code. Fascinating! In six short sentences, Hammurabi created the world’s first written building code that comprehensively covers all matters related to construction. He captured so simply the essence of the arrangement: Obligate each side to the other and inflict equal punishments on the purchaser and provider so that both are burdened to ensure a satisfactory outcome.

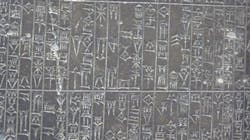

After reading these six laws I couldn’t help myself, I had to see how the modern version compared with the original. While the intent was the same — to ensure that the buyer received from the builder a structurally sound home — that is where the similarity stopped. The largest difference of course was in length. What originally took up a few lines on a stone tablet now numbers hundreds of pages. The level of detail is also vastly different.

Certainly, building science accounts for the major difference in the length and the level of detail in modern building codes. The earthen bricks and wooden doors of Hammurabi’s time have given way to myriad components that make up the modern house, and for each piece there are codes, regulations and standards governing use and installation.

This is as it should be, for like Hammurabi’s six rules, the intent of every code, regulation and standard is to assure builders and buyers that these elements, if followed, form a foundation to create a home satisfactory to both parties. Too often, however, builders see codes as simply one more way government regulates their work and drives up the cost of housing. Buyers view codes as the minimum standards for acceptable construction, and they expect more than the minimum.

In these times, intent and interpretation divide builders and buyers. Without that common foundation, getting to a satisfactory outcome is risky and maybe just as costly.