Bryson Garbett’s split life as a builder and a philanthropist gives him a unique perspective on the issue of immigration reform.

In Utah, where his company—Garbett Homes—closed 350 houses last year, he is feeling the pinch of a tight labor market. Plumbers, electricians, and HVAC contractors are harder to find, he says. “But it’s not just skilled, it’s all kinds of labor—packing foundation forms, hanging drywall, landscaping,” Garbett says. “In the past, that was being provided by immigrant labor.”

Many of those workers were from Mexico, a country that Garbett knows well. He is also the founder of Foundation Escalera, a nonprofit that builds schools in rural Mexican villages and provides scholarships to young Mexican students so they can attend high school. “Mexicans would rather stay in Mexico and work,” he says. “They don’t want to take the risks involved in crossing the border. They only come here because they are desperate.”

The situations he sees both at home in Utah and in Mexico leaves Garbett frustrated with the country’s current immigration policies, which he feels are unworkable for businesses and immigrants. “They provide an important part of our economy, especially in construction,” he says. “But we make it so difficult for them. Anything would be better than what we have now.”

He’s not the only one who feels this way. After a bruising recession, builders and their subs are now bracing for the inevitable moment when the recovering demand for new homes will outstrip the limited number of construction workers available.

“We’re already bumping into the beginning of it,” says Mike Benshoof, chief operating and financial officer for Classic Communities in Harrisburg, Pa., and Red Door Homes, a scattered-site builder in eight states. “It starts with ‘I’m not interested in driving that far for a job,’ and then you get the price increases. We’re hearing ‘I’m not interested in driving that far’ for jobs that a year ago they would have jumped all over.”

Others are already experiencing multiple labor pains. In the Dallas/Fort Worth metro area, labor issues are “limiting the number of houses we can build and inconveniencing our buyers due to delays. The local economy is negatively impacted because consumers are experiencing costs and prices that are being artificially inflated,” says Don Dykstra, president of Bloomfield Homes in Southlake, Texas, which hopes to sell 700 homes in 2014. Lastly, “suppliers and contractors that have the capacity to handle additional work are missing out because the overall market is constrained by not enough available workers in critical trades.”

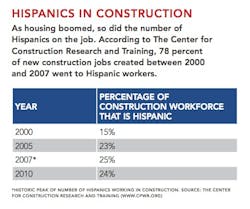

Such shortages are real. In 2007, at the height of the boom, the construction industry employed nearly 8 million people, with an estimated 25 percent of them Hispanic. In early 2014, construction employment is down to fewer than 6 million, and builders worry that many of their former workers—both legal and illegal immigrants—will not be returning to their job sites, leaving them scrambling.

“This is an ongoing issue, because the residential construction workforce and the marketplace of the 1990s and 2000s definitely benefited from immigrant labor,” says Doug Bauer, CEO of TRI Pointe Homes in Irvine, Calif., whose firm expects to close 660 homes this year. “But the long recession has really deterred workers from coming back and contractors from growing because they got whacked so hard last time.”

Immigrants on the job

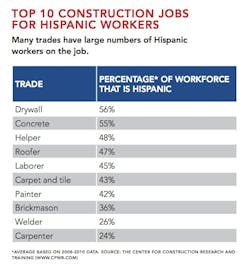

Visit any new home under construction, and the connection between the housing industry and the immigration issue becomes immediately obvious. Overall, an estimated one-fourth of construction workers are Hispanic; and in some trades, like drywall and concrete, Hispanics represent more than half the workforce, according to The Center for Construction Research and Training (see chart on page 40).

And the housing boom couldn’t have happened without them. As builders and subcontractors rapidly scaled up, Hispanic workers occupied roughly 78 percent of the new construction jobs created between 2000 and 2007, according to the Center.

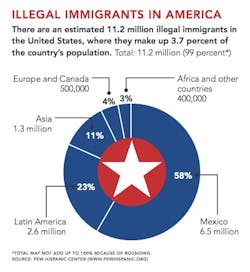

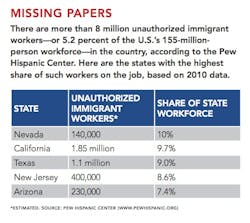

However, many of them were working illegally. Precise numbers are difficult to find given the reality of undocumented immigrant life, but researchers believe there are an estimated 8 million unauthorized workers in the United States, which represents 5.2 percent of the U.S. workforce. Numbers from the Pew Hispanic Center also suggest that many are Hispanic: People from Mexico and Latin America add up to 9.1 million of the country’s 11.2 million undocumented immigrants. Within the housing industry, as many as 22 percent of workers are unauthorized, according to HousingEconomics.com.

But as housing jobs vanished, so did many of these workers. They moved, escaping unemployment and anti-immigrant sentiment in places like Arizona, Alabama, and elsewhere to chase jobs in the roaring world of oil and gas exploration in Texas and North Dakota, among others. In places like Bismarck, N.D., “It’s hard to get trades,” Benshoof says. “Oil company trucks will drive up and say, ‘Who wants to make six figures on an oil rig?’ Workers will literally drop their tools and walk off the job site.”

Stalled reform

One solution to builders’ labor woes? Comprehensive, federal immigration reform, which could support the economy by improving the size and stability of the construction workforce.

Policy changes at the federal level would also eliminate the confusing patchwork of state and local laws governing immigrants in recent years. In Arizona, where undocumented workers represent 7.4 percent of the state’s workforce (the fifth-highest share in the nation), voters in 2010 passed a controversial law that requires law enforcement to check the immigration status of everyone they stop, hold, or arrest; noncitizens must also have their immigration papers with them at all times.

Arizona isn’t alone in tackling the issue of illegal immigrants. Since 2010, more than a dozen other states have adopted or explored similar laws. “The fact that states and localities have been trying to take up immigration on their own proves the point that this is a federal issue that needs to be addressed in comprehensive ways,” says Catherine Singley Harvey, manager of the Economic Policy Project at the National Council of La Raza, a Washington, D.C.-based organization that advocates for Hispanics’ civil rights.

Last year, a bipartisan group of eight U.S. senators tried to do just that. Known as the Gang of Eight, they developed a comprehensive immigration bill that included a number of reforms, such as a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants already in the country, a better employment verification system, and an expanded guest worker program for low-skill workers such as construction laborers.

But their efforts stalled, thanks to political gridlock in Washington. “Unfortunately, what this country needs is real leadership,” says Bauer, who is exasperated by the lack of action on both immigration and budget reform.

Unfortunately, builders such as Bauer will probably remain frustrated for months to come.

While NAHB chief lobbyist Jim Tobin says he has seen “movement” on the issue of immigration reform in the U.S. House of Representatives, he doesn’t anticipate any votable bill to emerge until 2015 or even 2016, when the next presidential election is held. “But this issue is not going away either,” he says. “Labor shortages are becoming more widespread across the country, and the construction industry needs to be able to tap into this employment market.”

Be our guest?

In the absence of full-fledged immigration reform, many builders are willing to settle for a guest worker program, which would provide a more steady, legal, and affordable source of labor.

“A guest worker program would be a great benefit to the industry because it would get people back into the trades and allow them to learn and be compensated for it,” says TRI Pointe’s Bauer. “I think it would improve both quality and quantity because you’ll be able to find good workers with the ability to be trained.”

The catch though, at least for builders, would be the number of workers allowed. Under the bipartisan immigration reform proposal introduced in 2013, the construction industry would have been granted 6,600 guest worker visas in the first year and up to 15,000 visas in later years.

Andy Warren, president of Maracay Homes in Phoenix, criticized those figures as unworkable in a newspaper interview in November 2013. “Fifteen-thousand guest workers for the nation’s growing construction industry is ridiculous,” Warren told The Arizona Republic. “That’s not enough workers to handle the building needs for one state, let alone a country.”

The NAHB agrees, advocating for a “market-based visa system” that would be more responsive to the housing market and builders’ labor needs.

Not everyone is convinced. According to La Raza’s Harvey, guest worker programs can be problematic because they create a group of “second-class citizens who are denied the rights of other workers.” To avoid that scenario, Harvey says such programs must include safeguards which protect visa holders from exploitation. “Temporary workers need to have the same rights as other workers, the opportunity to earn citizenship, and the visas need to be portable from employer to employer so that the visa does not tie a worker to an abusive employer,” she says.

Some builders have reservations, too. “It would really depend on what the legislation looks like,” Benshoof says. “With every well-intentioned change—even if it is perfect reform—there are always unintended consequences.”

Others believe that’s a risk worth taking. “Immigration in the past is something that the United States has done better than anybody,” Garbett says. “Building a wall [to prevent illegal immigrants from crossing the border] and thinking that will solve our problems? That’s crazy. What a waste of money.” PB

Sign-up for Pro Builder Newsletters

Get all of the latest news and updates.