Lots with tight setbacks raise many design issues including aesthetics, privacy, light, views, and parking. Then there are zoning ordinances and building and fire codes to consider. Suburban infill locations, too, are subject to restrictions on the amount of front-, rear-, and side-yard space as well as the height of the structure. It takes design creativity, fortitude, and flexibility to cope with these situations.

“Since we build mostly in town, we encounter a lot of one-off lots,” says Jim LaVallee of Epic Development, a spec home builder in Atlanta. To change the existing setbacks of a particular lot, Epic has to apply to the city for a variance, showing that the original conditions present a barrier to sensible design.

LG Development Group specializes in high-end custom homes in desirable Chicago neighborhoods. “A standard Chicago lot is 25 feet wide and 125 feet deep,” says LG partner Brian Goldberg. “A lot of older homes were built right up to the lot line. It’s rare that we can actually run with the existing setbacks, so we maximize the width of each home.”

Residence 1 at Momentum, a Trumark Homes community in Milpitas, Calif., is designed so that neighbors can’t see into its private side yard. Main living areas are on the first floor, bedrooms are on the second floor, and the third floor can be finished as a bedroom suite with either a sitting room or family room. Photos: Christopher Mayer Photography

Los Angeles also takes a formulaic approach to setbacks, notes developer Casey Lynch of LocalConstruct. “Single-family lots are commonly 5,000 square feet and 25 feet wide,” says Lynch. “In neighborhoods such as West Hollywood, people are tearing down 1,500-square-foot, Spanish-style bungalows that were built in the 1930s and 1940s. They then build 4,000-square-foot, two-story, super-modern houses that are pushed to all four setbacks. You can literally reach out and hand your next-door neighbor the salt shaker.”

Lynch says there has been pushback from the city against this trend in the form of “anti-mansionization” laws. People do buy the gargantuan houses, but in his opinion, they’re unattractive and don’t fit within the neighborhood context.

LocalConstruct is using L.A.’s small-lot subdivision ordinance to develop medium-density, detached homes that respect the architecture of the older homes around them. The small-lot ordinance allows zero side setbacks, though the fire code prohibits windows or other openings that are within 5 feet of a property line. “To deal with that, you have to use treatments like tempered glass or water curtains, which are very expensive,” Lynch says.

What drives much of the development in Los Angeles and other cities is parking. “You have to provide two covered parking spaces for a single-family dwelling in L.A.,” he says. “That has a lot of implications for the size of what you can build and how much you can push the envelope with setbacks.”

Rezoned for high-density detached

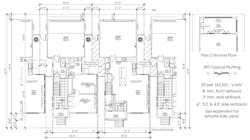

Side setbacks at Momentum max out at 4 feet, requiring KTGY Group to balance the desire for natural light with the need for privacy.

Trumark Homes, Danville, Calif., rezoned a 7-acre commercial property in Milpitas, Calif., to fill a void in the market for housing. Because the urban infill site is transit-oriented, the city of Milpitas wanted higher-density product, and in a rare move, approved Trumark’s proposal for a mix of housing types that met those density goals. The community, called PACE, includes 91 three-story townhomes and 43 detached homes.

“It’s Silicon Valley, so our buyers are primarily high-tech engineers—mostly young families or couples starting a family,” says Trumark CEO Mike Maples. “Many are relocating from international markets and have extended families that visit on a six-month visa. That’s why we provide bedroom suite options and dedicated living areas for extended family members.”

At Momentum, the single-family detached portion of the community, two plans are offered: Residence 1, which is 2,250 square feet, and Residence 2, which is 2,497 square feet. Both are three-story homes with rear-loaded, two-car garages.

Momentum at PACE, which was known as Contour in the early planning stages, employs a Z-lot concept that offsets the façades for greater visual interest. Illustration courtesy of KTGY Group

“[The second floor] is a knockout space that reads front to back,” says Jill Williams, principal of KTGY Group’s Oakland, Calif., office. “It has bifold doors off an entertaining deck that’s 20 feet wide and 81/2 feet deep.”

The density of the detached housing is 14.5 DUA. Williams says the lots are fairly uniform: 29 feet wide by 64 feet deep. “We tried to ‘Z’ them a little bit—jog the property lines to get a more interesting read and a bit more frontage.”

The setbacks are a minimum of 8 feet in the front and 3 feet in the rear. Side setbacks are either 6 inches, 31/2 feet, or 4 feet, and there is a use easement for private side yards.

Residence 2 has a large deck off the living room that can accommodate a dining table for eight, plus a few club chairs for guests who want to watch TV while outside. The main living areas are on the second floor; a bedroom, full bath, and den are on the first floor; and another bedroom suite is on the third floor, along with the master suite.

“It was a new take on what we’ve done before,” Williams says. “We wanted to get the most out of the lot without sacrificing the ability to have windows on all four sides.”

KTGY got involved early on “so we could marry up the land plan and the architecture and really study the floor plans on all three levels,” she says. “There’s an active side of the home and an inactive side. The latter side has windows, but they tend to have higher sill heights to provide visual protection from neighbors. And in a few cases, such as in one of the master baths, we decided to obscure the glass.”

Since Momentum opened this past April, Trumark has sold 13 of 14 homes in phase one. Due to the fast sales pace, the builder has raised prices, which now range from $865,000 to $905,000.

Tight squeeze

LG Development built this Chicago home on a 32-foot-wide lot with characteristically tight setbacks. The striking limestone façade makes it stand out instead of blend in with its very close neighbors. Photo courtesy of LG Development Group

Standard Chicago zoning requirements for detached homes call for a 30-foot height limit; a minimum 25 foot front-yard setback; and a minimum 50 foot rear setback. The combined width of the side setbacks must equal 20 percent of the lot width, with neither setback being less than 2 feet.

The city has a process called an “administrative adjustment” that, under certain conditions, will authorize setback changes. It’s a less-involved, shorter process than filing for a variance, and the adjustment can be approved by the alderman and the zoning administrator. “If I want an extra 6 inches on one side, that’s deemed an administrative adjustment,” says LG Development partner Brian Goldberg. “But if I want to build all the way to the lot line on one side, that’s a variance.”

Proper orientation is critical. “In the city you’ve got four possible orientations: north, south, east, or west,” he says. “You have to consider the sun’s progression during the day during both the winter and summer solstices.”

LG considers the height and proximity of neighboring properties as well as the materials of which they’re constructed. “Let’s say there’s a brand-new, modern glass house that’s 40 feet tall on one side of our lot, and a 23-foot, 100-year-old masonry cottage on the other,” he says. “We try to calculate how much longer the cottage will be standing.”

On 25-foot lots, the front door is rarely centered on the façade. “You have to decide if the front door is going on the right side or the left,” Goldberg says. Typically the stairs and hallways are aligned with the front door, “so it’s like picking which side you want your bedroom to be on. We try to find the side that gets more air and sunshine.” Outdoor space is placed at the rear of the home, where the setbacks are deeper.

Award-winning design on a skinny site

Epic Development obtained a variance from the city of Atlanta to reduce front, rear, and side setbacks and enable construction of this 20-foot-wide modern home. Photos: OBEO

Epic Development is an expert in building on urban infill lots that have a variety of constraints (narrowness and steep grades, to name two). One of Epic’s recent successes is a home on a 27-foot-wide, 92-foot-deep lot close to popular restaurants and taverns.

“With the standard setbacks, the home could only be 13 feet wide, which isn’t practical,” he says. “I’ve seen those done, but it gets very linear.”

Epic applied to the city of Atlanta for a variance to reduce the required front-yard setback from 30 feet to 15 feet, and reduce both side-yard setbacks from 7 feet to 31/2 feet. They justified the request by indicating that the lot is only 92 feet deep and slopes steeply away from the street, which, combined with the rear-yard setback, made the lot unbuildable.

Plans purchased online were modified and window placement adjusted to allow more light into living areas and take better advantage of views. There’s a bedroom and full bath on the garage level, living areas on the main level, and two additional bedrooms on the top floor.

The two-story, single-family home is 20 feet wide and 1,800 square feet, with a tuck-under garage. “The elevation matters from the standpoint of architectural appeal, but we also wanted to make sure the rooms had enough light and the views were pleasing,” LaVallee says.

The home won an OBIE Award from the Greater Atlanta Home Builders Association and was sold prior to completion.

How to Cope with a Tight Situation

Bond with the neighbors. With neighboring homes just a few feet away on either side, construction activity on a tight lot is bound to create stress. Jim LaVallee of Epic Development, Atlanta, emphasizes the importance of getting the neighbors onboard.

“It’s wise to invest time with them before you start so you can stay on friendly terms,” he says. “A couple of bottles of wine, some sports tickets, or dinner at a nice restaurant are good investments. You also need to assure them of your commitment to restore any damage when the project wraps up.”

Brian Goldberg of LG Development Group in Chicago adds, “Don’t do anything without the cooperation of the neighbors and the aldermen. You don’t want to be an adversary.”

Make sure trade contractors and suppliers know the rules. Remind them repeatedly about the proper location for parking trucks, job-site cleanliness, starting and ending hours, and working on weekends. “A 5 a.m. delivery on Saturday will ruin the neighbor’s day and your weekend because you’ll be doing a lot of damage control for the next few days,” LaVallee says. “It’s hard to compensate someone for lost sleep on their day off.”

Expect to invest more time and money. Add several months to your schedule for the variance application process because there are many meetings to attend. It will also cost you more. As LaVallee says, “You have to pay taxes, keep the grass cut, and so forth for the additional three or four months it takes to get a variance.”

Do your homework. Become familiar with the appeal process and the nuances of zoning and other ordinances. It’s advisable to have an attorney walk you through it the first time. PB

Sign-up for Pro Builder Newsletters

Get all of the latest news and updates.