When done right, industrialized (or off-site) construction can shorten production cycles, boost quality, and reduce the labor needed to build a home. And these advantages are prompting more and more builders to investigate how an industrialized production model could work for them. “This is the future of residential construction in the U.S.,” says Rowland Bates, president and CEO of New Seabury Homes, in Mashpee, Mass.

Bates admits there’s a learning curve to optimizing off-site construction to maximize its benefits and mitigate its pitfalls. As such, it will take time before a critical mass of the housing industry utilizes the technology and catches up to early adopters. “It may take 10 years to get there,” Bates says.

We spoke with a handful of home builders at various stages of transitioning from traditional stick-built, on-site production to some form of industrialized construction. Each had learned important lessons and had observations to share.

RELATED

- 2024 Housing Giants list

- Your Road Map to Off-Site Construction and Modular Homes

- Introducing Modular Construction to a New Labor Force

LW Development: Finding the Right Solution

Based near Oklahoma City, Okla., LW Development builds affordable workforce housing and has completed 600 units in its home state and in Kansas. CEO Lance Windel is convinced that using volumetric modular construction is key to profitability in this market segment, despite his failed attempt with another off-site approach a few years ago.

“We tried panelization of walls ourselves and failed miserably,” he says. “We didn’t know what we were doing.” The main problem, he points out, was that the panel design turned out to be too complex to assemble efficiently on site. But that experience didn’t quell Windel’s enthusiasm for off-site construction. The company bought an old railroad car factory and converted it into a modular manufacturing facility last year. The building is well-suited to its new purpose, having come with “overhead cranes galore,” Windel says.

Instead of spending big to outfit the space, his team MacGyvered only what was needed to enable production. They hand-built wooden tables and used an industrial skate dolly and wooden jigs to mark and measure materials, thus keeping the company’s capital investment to a minimum. “We bought it with no venture capital,” Windel says. “Sixty days later, we completed a three-story apartment complex.”

Having learned from his previous attempt, Windel simplified and standardized LW Development’s home and component designs to better suit a modular approach. That also reduced materials waste—a key benefit of off-site construction that enables the company to deliver attainable housing.

A few months later, the facility added a printer to mark lumber and drywall for more precise cutting, which further increased waste reduction. “You can get a basic printer for about $50,000, and one that also cuts for $100,000,” Windel says.

Windel advises builders getting started with off-site methods to first estimate their construction backlog and to balance production with demand. It’s also wise to get price quotes from trucking firms up front if you don’t have the vehicles to transport components yourself. “Provide trucking firms with the dimensions and approximate weight of the panels or volumetric units to get an accurate quote,” he recommends.

Modular also can really pay off on large projects in remote areas where available labor is tight, according to Windel. On a major apartment complex project near Midland, Texas, LW Development used volumetric components so it wouldn’t have to pay to house laborers for the couple of months it would have taken to frame the project in a traditional manner. “You can start small with panels,” Windel says, but to get the most out of off-site, volumetric is the way to go.”NOW Communities: Keeping It Simple

Dan Gainsboro, owner and CEO of NOW Communities, in Concord, Mass., has been kicking the tires on off-site building for several years. His mixed views on the technology are based on his research and a few proof-of-concept forays.

In 2009 and 2010, Gainsboro expected to use off-site methods for a compact neighborhood of 13 New England cottage-style homes in Concord. As a test case, one home was constructed using an off-site panelized approach. The home itself was cost-effective to build—it even achieved a stringent high energy-efficiency standard—but off-site methods didn’t really suit the project’s scale. “Pocket neighborhoods are simply more expensive to build,” he says.

Still, that home took just 2 1/2 days to frame versus the 2 1/2 weeks it took to stick-build the others. Gainsboro also was impressed by how well the panelized home performed on its blower door test, despite having a complex roofline.

Since then, more off-site providers have emerged in New England, resulting in increased competition, lower costs, and greater capacity.

Gainsboro intends to use factory-built wall, roof, and floor assemblies to construct a multifamily building in Devens, Mass., within a former Army base, and is considering using partially finished panels for the final phase of that project, which is composed of 26 mid-market, single-family homes.

“Panelization works when you have simple, repetitive designs with straightforward engineering,” Gainsboro says. He finds the advantages of precisely constructed components built in a controlled environment with faster schedules compelling, as is the precision that mitigates on-site changes—a common stick-building issue. “Field changes are anathema to factory-built assemblies,” he points out.

The scheduling advantage isn’t as pronounced as it used to be, though. Framers are now panelizing components on site and can frame a home in a week. “I’ve learned that the set crew really matters,” Gainsboro says of the carpenters and laborers he hires to place and assemble factory-built panels. “If you don’t have a good set crew, you could have chaos.”

Bayview Homes: Doing More With Less

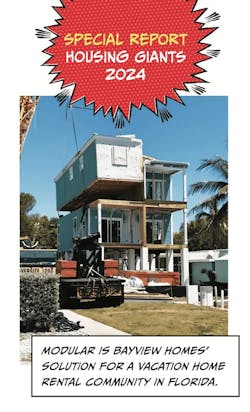

Bayview Homes, in Tavernier, Fla., is a pioneer in off-site development, placing its first modular home in the 1990s. Since then, the company has set more than 500 such units across the U.S., including single-family homes from 1,200 to 4,800 square feet, as well as hotels and apartments. It’s currently developing a 20-unit vacation home rental community in Florida.

“We still build site-built homes, but our emphasis has been on modular homes,” says company manager Jim Saunders, a practice driven by the desire to deliver more homes built by fewer people.

Initially, Bayview engaged providers of HUD Code manufactured homes (mobile homes) that agreed to convert part of their factories to produce modular units specifically for Bayview. But such arrangements became problematic, Saunders says, because the manufacturers couldn’t always keep up with Bayview’s production schedules while still meeting their own mobile home demand. Bayview then transitioned to partnerships with providers focused solely on modular. Today, its primary supplier is Affinity Building Systems, in Lakeland, Ga., which is providing modular 3,600-square-foot units for the vacation home project.

“We collaborate on designs,” Saunders says. “If they have issues, our engineers work with them to come up with a design solution.” If they can’t arrive at a mutually acceptable solution, the Bayview team revises the design to eliminate the problem.

Bayview also has cultivated long-standing ties with local framers, electricians, plumbers, and other trade partners for the on-site work required to ready the site for modules and to complete their assembly.Those ties with dependable contractors that know Bayview’s requirements and work for a consistent base price has been key to the success of the builder’s modular strategy. “It’s particularly advantageous on projects in the Florida Keys, where the cost of labor is very high,” Saunders says.

An overlooked advantage of modular, he adds, is the relative ease of project administration. “Stick-built is much more intense to manage, with all of the scheduling and coordination of labor and materials,” he says. “With modular, there’s up to 30% less office labor and cost involved.”

Saunders also uses pre-set formulas based on a home’s size to price out modular projects. “I can do a representative budget in three days,” he says. “Site-built clients have to wait a month for a budget and may lose some enthusiasm over that time.”

New Seabury Homes: Playing Ahead

For a new luxury-home community in Pinehurst, N.C., modular production is very much part of New Seabury Homes’ development plans, says CEO Rowland Bates. But the builder is taking it slow, partnering with a modular provider on a few “test” homes with an eye to aggressively scaling up later. “If it works out, we could be producing 100-plus homes that way in a couple of years,” Bates says.

The reason? “Speed and labor, but most importantly, quality and energy efficiency. Building in a factory environment will give us far more control over those factors,” he says.

For the test homes, the provider will deliver finished wall panels with pre-installed runways for electrical and plumbing and chases for ductwork.

Bates hopes to start construction of those homes and others in the community by the fourth quarter of 2024. “Our intent is to build weathertight frames and interior partition walls off site, deliver and set them on site in approximately one week, and then finish the homes inside using traditional construction techniques and finishes.”

A big challenge, he says, will be educating homebuyers and trade partners about off-site construction and how it, ideally, improves home building. “Buyers hear ‘modular’ and think ‘double-wide trailer,’” he says. “They think they aren’t going to get a good product, so we need to confirm that the homes we build are better than stick-built.” And while trades are concerned off-site methods will cost them business, Bates intends to show they can actually make more money by boosting productivity using modular. “We must select contractors that are open to change,” he says, but also not push too hard too fast. “It’s smart to walk before one runs.”

His vision extends well beyond his next community. The company is owned by a large investment firm with the means to finance a wholly owned modular facility, but the bigger question is where to locate it. New Seabury Homes historically works across a fairly wide geographical area, and panel or modular facilities need to be located within a region of concentrated demand to make the economics and logistics work.

Bates says he may focus more activity in North Carolina to make a self-owned factory there financially feasible. For now, existing factories in Virginia and Pennsylvania will meet the company’s off-site needs.

“We believe that 10 years from now, everyone in the U.S. will build using modular or panel techniques,” Bates says. “And we want to be way out in front of other national builders in what we expect will be a paradigm shift in construction processes for new homes in the future.”

The Fallout From Off-Site Failures

The highly publicized business failures of well-funded off-site system providers Katerra in 2021 and both Entekra and Veev in 2023 doesn’t mean the modular concept can’t work.

In fact, those collapses may be good for the industry in the long run because they illustrate what start-up providers shouldn’t do.

“Katerra wanted to displace the supply chain entirely,” says Currey Cornelius, managing director at financial advisory firm Whelan Advisory Capital Markets. “They bit off too much and tried to do too much with technology.” The company’s big cache of venture capital worked against it, he says, as it invested liberally in high-priced equipment and facilities. “Factories are capital-intensive. To build scale over fixed costs takes time and patience,” he points out. “And the industry is volatile; overhead expenses don’t stop if your schedule is disrupted.”

Entekra ran into similar problems. “They had a nice factory, but the machinery was probably too expensive [for a price-sensitive target market of high-volume production builders],” Cornelius says.

In addition, the new-home market in California, where Entekra and Veev focused their efforts, has struggled during the past few years, reducing demand for what those providers offered in terms of technology and product.

Cornelius also believes Veev tried to tackle too many sectors—luxury single-family, multifamily, and townhomes—resulting in a lack of focus, which made it difficult to develop a profitable business model.

RELATED

- Q+A With Brent Wadas: How BotBuilt Is Automating Home Construction

- Volumetric Building Companies' Vaughan Buckley on Restarting a Former Katerra Factory

- On-Site vs. Off-Site Construction Methods: How to Make the Right Decision

It didn’t help that all three companies employed, or were led by, key decision-makers from outside of the U.S. home building industry. Undoubtedly, that lack of industry-specific expertise played a role in their failures. “If they had consulted with builders more deeply to find out what they wanted instead of imposing their vision on them, they could have been successful,” Cornelius says.

The three companies intended to manufacture the whole house off-site, but home builders and their trade partners weren’t ready for or willing to adjust to that degree of sophistication. By contrast, off-site suppliers that take a collaborative approach and tailor their product to each builder have a better chance of success, according to Cornelius.

“Modular suppliers should empower the industry rather than trying to disrupt it,” he says. Several prominent builders—Clayton Homes, Skyline Homes, Goodall Homes, Van Metre Homes, and Billa Homes, to name a few—are either creating their own off-site facilities or are forging ties with third parties, and that approach appears to be working well. —P.F.

Why Not Off-Site?

More than 70% of this year’s Housing Giants build homes with little or no customization, and 25% report struggling with higher labor and materials costs. Yet less than half have engaged in any sort of off-site building method to address production hurdles that could help close the housing supply gap and alleviate the affordability crisis. The main barrier to adoption? A perception that off-site costs more than stick-building.

Based in the Boston area, Peter Fabris is a freelance writer who has covered the built environment for more than 15 years.