The tiny-house movement has been gathering steam for about a decade, powered by consumers who wish to simplify their lives. If the popularity of TV programs such as Tiny House Nation is any indication, the movement is stronger now than ever. Overwhelmed by debt and large, overstuffed houses, many Americans are paring down their possessions and moving into dwellings that are as small as 200 square feet.

“Tiny houses [are] a healthy reaction to the supersized culture that we Americans have had for so long, not only in food but in housing,” says Chapel Hill, N.C., architect Arielle Condoret Schechter. “We have all these extra spaces we don’t use; why should we pay for heating and cooling them?”

Miami architect Marianne Cusato, designer of the Katrina Cottage, adds, “We’re surrounded by piles of things that we haven’t done and reminders of things we should be doing. We’re paying for things that we can’t afford. So this idea of a non-cluttered life is really refreshing.”

Tiny houses aren’t just for proactive downsizers. Some developers and designers believe they could be an answer to homelessness and poverty. Tiny homes could also be absorbed into the mainstream housing market as a solution for seniors, singles, and anyone else whose income is insufficient to purchase a larger home.

While the zoning in many municipalities prohibits accessory dwelling units (ADUs)—smaller structures built on the same lot as the primary residence—some cities, such as Portland, Ore., have relaxed those restrictions. The regulatory changes have opened up a new avenue for tiny houses, a crucial one for the aging population, Cusato says: “They’re not only an alternative to expensive assisted-living facilities; they also integrate older people with their families and the community.”

Geoffrey Warner, founder of Alchemy Architects, in St. Paul, Minn., notes that tiny ADUs could also be rented to college students who need to live near universities, or accommodate adult children returning to the nest. Alchemy’s weeHouses range from 300 to 850 square feet.

Another variation on the tiny house is the micro unit—a small studio apartment typically less than 350 square feet, with a fully functioning and accessibility-compliant kitchen and bath. A recent study by the Urban Land Institute, “The Macro View on Micro Units,” found that there’s a segment of renters interested in micro apartments in exchange for a lower monthly rent.

View a slide show of the tiny house projects mentioned in this story, including plans, elevations, built projects, and interiors

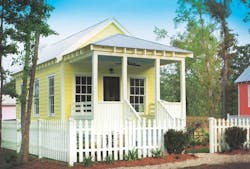

Marianne Cusato's Katrina Cottage measures 308 square feet and, depending on local costs, runs about $38,000 to $40,000 to build, excluding foundation and land.

Tiny, But Not Primitive

According to TheTinyLife.com, a Web resource for those who want to build small, the typical tiny house is approximately 100 to 400 square feet. Some are placed on permanent foundations, but most are set on trailers and legally classified as RVs. Unlike RVs, however, tiny homes look a lot like their larger counterparts, with 12/12 pitch roofs, turned-post front porches, cedar siding, and broad eaves. The range of architectural styles has expanded in the last 10 years to include clean-lined, modern houses like the ones Schechter designs. The tiniest models have sleeping lofts, but there are also versions with main-level bedrooms.

Living tiny doesn’t have to mean roughing it. Even a home of less than 200 square feet can be fitted with a dishwasher, a shower, and a nearly full-size propane cooktop and oven. Schechter’s Micropolis Houses are larger than most tiny houses, ranging from 785 to 1,272 square feet, with two bedrooms and a deck or screened porch.“I started designing the Micropolis Houses about eight years ago because I didn’t see any modern tiny houses,” she says. Recently a client convinced Schechter to set up a booth at a senior housing expo in Chapel Hill. “There were other tiny-house companies there too, but my booth was completely swamped. I couldn’t believe the response.” Schechter has discovered that the appeal of her little houses goes beyond the 65-to-90-year-old crowd. “I’ve gotten calls from all over the world, many from people in their 30s who are into the cool factor,” she says. “The homes offer a custom look without the cost of full architectural services.”

One of the keys to good tiny-house design, says Schechter, is multiple uses for areas—nooks instead of separate bedrooms; surfaces that pull away or swing down; a kitchen table that becomes a desk; a bed that doubles as a sofa during the day. “And you have to tuck storage everywhere,” she says. “My smallest model has super-thick walls with built-in storage.” Tiny-house TV shows spotlight other creative storage ideas such as under-stair drawers or cubbyholes. Because the Katrina Cottages have 9-foot ceilings, Cusato uses the space above closets for extra storage. “When you can, add a little niche here and there where you can have some open shelves or a broom closet,” she says.

The tiny house interior of the Axia from TechDwell features clerestory windows and two sets of double doors, which make the interior feel bright and spacious.

Factory Process Yields Quality and Quantity

Mass production is the next logical step in reducing the cost of tiny homes. Jay Shafer, founder of Four Lights Tiny House Co., in Cotati, Calif., is talking to an RV manufacturer about prefabricating his houses (see “Conceiving a Tiny-House Village,” below). TechDwell, a Portland, Ore.-based company, is already doing it. The company offers the 192-square-foot Axia, which has a prefabricated modular steel frame, a precast concrete pin foundation system, and a 4-by-16-foot exterior deck. Production of the frame, foundation, and panelized wall and floor systems is outsourced.

TechDwell’s Dave Carboneau says that the first Axias were built in Haiti for survivors of the 2010 earthquake. The company is planning demonstration projects in Honolulu, Portland, and San Jose, Calif., where the units will serve as housing for the homeless. “They’re also a great solution for people earning $10,000 to $15,000 per year who can’t afford anything larger,” says Carboneau. The Axia is base-priced at $12,500 and is easy to assemble, with a structure that has been tested to withstand seismic forces. The 12-by-16 modules can be combined to form larger units, including a two-story version.

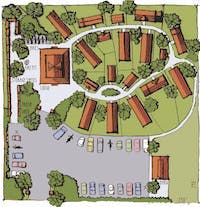

The visionaries who started designing tiny houses years ago have seen a spike in interest from builders and developers. Cusato, who offers eight Katrina Cottage plans ranging from 308 to 1,807 square feet, says she’s selling more of the 300- and 400-square-foot plans: “I got a call from a developer who wants to do a little cottage court in New Orleans for short- and long-term rentals.” Schechter has been contacted by a builder who’s interested in doing a tiny-house development in North Carolina. Alchemy Architects, too, is working with builders and developers on tiny-house communities.

“You’re talking about a $100,000 house rather than a $400,000 house, which is a little easier to bankroll,” says Alchemy’s Warner. “Some developers tell us, ‘We’re finding that in this really nice community, we don’t have anywhere for our young people or our workers to live that’s affordable and has integrity or dignity.’”

Local ordinances and building codes are often the biggest obstacles to building tiny. Many tiny-home owners build on trailers, but because parking can be difficult to find, they park on land owned by friends or relatives. Developments like Shafer’s, which promote social interaction and allow residents to own their homes and land, will show that a tiny home can be more than a quirky, one-off solution.

Conceiving a Tiny House Village

What It Costs to Build a Tiny House

Tiny houses aren’t necessarily inexpensive to build. According to TheTinyLife.com, the average cost of an owner-built tiny home is $23,000. As with the construction of any home, there are variables to consider such as the foundation, utilities, site work, and delivery. Costs can be reduced by using salvaged materials, but the level of finish and optional features—such as composting toilets, solar panels, fireplaces, and in-floor hydronic heat—will obviously result in a higher price tag. For Alchemy Architects’ 450-square-foot, one-bed, one-bath weeHouse, buyers can expect to spend between $110,000 and $120,000 on the low end and between $125,000 and $155,000 on the high end.

All weeHouses come standard with custom white oak floors; a three-quarter bath with a dual-flush toilet; Duravit and Kohler fixtures; Andersen windows; wood or steel siding in a choice of colors; high-efficiency spray-foam insulation; and add-ons such as a California-approved sprinkler system, as needed. Consequently, it makes more sense to use factory-built components and modules and to think in terms of more than one house at a time. “Although weeHouses are conceived as stand-alone homes, they become even more compelling when planned in developments,” says Alchemy’s Geoffrey Warner. “Multiples, clusters, and shared-wall arrangements can significantly reduce costs from the examples [given here].”