2019 Housing Giants Report: Easy Does It

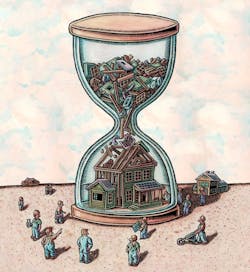

Traditional home building isn’t easy. Not only is it done outside, it requires coordination of perhaps two dozen types of specialty trade contractors to deliver homes on schedule and on budget.

That model has served the housing industry well enough for nearly a century, but its future is beginning to strain under the weight of a chronic shortage of skilled construction labor driving longer cycle times, rising costs, and less profitability for builders.

True disruption of that status quo probably won’t happen all at once; more likely, current methods and materials will evolve incrementally. Builders always look for ways to cut construction costs, of course, but many aren’t ready to dive into the holistic change of modular or even whole-house, off-site panelization; they’re far more comfortable taking intermediate strides away from stick building.

“A lot of builders will tell you, ‘We’re not pioneers, we’re followers’,” says MacGregor Pierce, a product manager at Hunter Panels, a polyiso roof and wall panel manufacturer based in Portland, Maine, repeating a refrain many providers of alternative construction solutions have heard for decades.

Modular and other turnkey off-site solutions are not how 80-plus percent of homes are built today, in part hindering widespread acceptance of those options. “[Builders] like to control all of the costs, and I think what we’re offering takes them as far as they want to go right now,” he says.

Between the current status quo and the blurry vision of a future that's fully factory-built lies a hybrid breed of so-called “integrated” products and systems engineered and manufactured to combine two or more materials and separate steps in the construction process.

The logic of integrated products is simple: By combining a few things into one, builders and their trade partners can theoretically save time and money, hasten homes to market, and boost profitability. The concept isn’t especially new; the introduction of insulated concrete forms (ICFs) and structural insulated panels (SIPs) to the U.S. market—both of which combine structural and insulating elements, eliminating one or more phases of construction—dates back to the 1980s. Yet both remain on the outskirts of single-family home construction.

More recent innovations, however, provide builders, trades, and the supply chain with more familiar, if still advanced, alternatives that enable greater productivity through fewer man-hours and reduced overall (if not initial) costs. Consider the advent of factory-built, wood-frame wall panels that combine studs and/or sheathing with insulation and air-sealing features; precut framing packages that reduce cutting, overbuilding, and materials waste; precast concrete foundation walls that install without footings; and plumbing pipe fittings that eliminate crimping and soldering, among other innovations.

And builders are paying attention.

In Home Building Construction Costs, Framing Leads

Of all the costs that go into delivering a house, more than half are for actual construction. And, of those costs, framing leads the way, so it’s a logical place to start looking for savings with alternative, if familiar, solutions. “Builders aren’t ready for a product that’s so disruptive they have to scrap what they’re doing,” says Michael Strohecker, a sales manager for Hunter Panels. “We’re looking at it from the standpoint of changing the industry slowly rather than taking that full leap [to modular construction].”

Hunter Panels’ latest offering, PURewall, is a quintessential integrated product. Developed by German company Covestro, a polyurethane foam manufacturer with its U.S. headquarters in Pittsburgh, PURewall combines a wood-frame wall panel with rigid foam insulation board as the exterior face and a layer of high-density spray foam insulation in the cavities (with room for wiring and plumbing runs), all done in a factory setting and then shipped to the jobsite for installation.

Both insulation layers purport to provide continuous thermal resistance while adding rigidity and air-sealing qualities that replace traditional wood-panel sheathing and housewraps—in short, combining five subphases (wall framing, cavity insulation, exterior sheathing, exterior insulation, and a weather-resistant barrier) and at least two trades (framing and insulation) that require multiple days on site.

The key message: labor savings. “We know builders looking at this [solution] who say they want to get to the point where they can turn a house in 30 days,” Pierce says. A production home builder in Sacramento, Calif., recently framed five homes with PUReWall, from which Hunter Panels is collecting data on time, cost, and other variables that affect cycle time, as well as on energy performance. Custom builders in Florida, the Washington, D.C., area, and Denver also have tried the system since its debut at the 2017 Pacific Coast Builder Conference.

Growing Pains and Cost Hurdles for New and Innovative Building Products

Despite logical (if not yet fully vetted) time and labor efficiencies for builders, PUReWall faces a vexing challenge: Not only does Hunter Panels need to win over builders, but it also needs to build a network of panel manufacturers to gear up for meeting local demand—if it comes. A builder doesn’t want a system that’s not available from a panel supplier, says Pierce, and panel manufacturers are hesitant to invest in a system builders aren’t asking for. Chicken, meet egg.

So the company must convince panelizers of the revenue potential in providing a value-added product that will more than pay back an up-front investment of perhaps $250,000 for a spray foam booth, air-handling equipment, and training. Hunter Panels also must recruit volume builders to create enough demand to further justify that investment.

“No panelizer is going to gear up and do this just because they think it’s a good idea,” Pierce says. “The builder has to ask for it. It’s well thought-out, but it’s not instant acceptance.”

A similar issue confronts Atlanta-based SharkBite and its EvoPEX Push plumbing system, which uses proprietary “push-to-connect” fittings to secure the inside diameter of cross-linked polyethylene (PEX) pipes without soldering, crimping, or any tools beyond a PEX pipe cutter. A green indicator appears on the fitting ring, signaling a secure connection. That cue is easier to see compared with an uncrimped ring and reduces installation errors. “The fitting helps contractors finish jobs faster, on schedule, and to do more with their existing crews,” says Christopher Carrier, U.S. marketing director for SharkBite's parent company, Reliance Worldwide.

Contractors who have used the fittings agree. “It has a quick learning curve and definitely made the jobs go faster,” says Clint McCannon, owner of Cannon Plumbing, in Braselton, Ga. He plumbed four new houses with SharkBite EvoPEX fittings, which the company provided at no cost as a trial run. However, McCannon hasn’t used the product since, nor have any of his home builder clients requested it.

Part of the reason why is that McCannon’s local suppliers don’t carry the line, and he says its up-front, materials-only cost is more expensive than other fittings. “It’s a great product, but with new construction, every builder wants to be as cheap as possible,” he says. “EvoPEX is not as cheap as possible.”

The relatively fast rise of PEX pipe’s popularity, from a 10 percent share of the housing market in 1997 to 70.6 percent by 2017, according to Home Innovation Research Labs, brought a lot of manufacturers to the table (SharkBite among them) and established a robust supply chain and industry standards that enable different brands to be used interchangeably. But the EvoPEX warranty drops from 25 years to five if used with another brand’s PEX pipes.

“We never priced it because when they told us their warranty drops down [with another manufacturer’s pipe], we [weren’t] interested. A company our size probably spends a million dollars a year on PEX piping and fittings,” says Keith Koster, quality assurance manager for Price Brothers, a Charlotte, N.C., contractor that will plumb 6,000 new homes this year. Price Brothers has been running PEX piping since 1995.

SharkBite is battling the perception that EvoPEX fittings cost more even though a check of price quotes from various plumbing supply houses shows a ½-inch tee connecter ranged between $4 to $7 each. Those prices were comparable with Zurn, Uponor, and other competitors, although some fittings were available for less than $2.

Correcting this misperception, as well as local supply and warranty issues, among plumbing contractors is critical to gaining market traction in new housing, as most plumbers make materials purchasing decisions on the builder’s behalf.

“EvoPEX is competitively priced, but the overall value of the system extends well beyond price because it enables the contractor to do more work with their existing crew, keeping the builder’s schedule on time,” Carrier says, adding that SharkBite partners with 95 of the top 100 plumbing supply distributors and they stock the fittings based on contractor demand.

New Materials' Promise Reduced Warranty Calls and Costs Plus the Benefit of Installation Efficiencies

While PURewall and EvoPEX try to gain market acceptance, other integrated structural systems that require less of a leap of faith and financial risk are gaining converts. Consider the Zip structural sheathing system from Charlotte, N.C.-based Huber Engineered Woods, which marries a standard-size engineered wood structural sheathing panel with an integral, vapor-permeable, weather-resistive barrier sealed at the joints with acrylic-based adhesive tape—combining at least two jobs into one while staying within a framer’s comfort zone.

For Green Brick Partners, of Plano, Texas, a diversified home building and land development company also active in Colorado, Florida, and Georgia, the selling point was performance first, speed second. Zip panels deliver better structural rigidity for wind resistance, a tighter building envelope for energy efficiency, and a better moisture barrier from the builder’s previous specification, all in one. Those benefits, among others, convinced Green Brick to switch to Zip despite an almost threefold cost premium over its previous solution for the same application. And 18 months after making the change, the builder saw warranty service calls to fix weather-related leaks drop 58 percent.

“Leaks hurt home builders. They hurt their reputations,” says Rick Davis, director of construction for two Green Brick brands, CB Jeni Homes and Normandy Homes, also in Plano. “The [integral] weather-resistive barrier is what did it for me and made it easier to sell to ownership.”

When Davis introduced the new material to his trades, there was some pushback. The previous spec—a foam-based panel—can be cut with a utility knife; Zip panels require a saw. The framers protested that working with the new boards would take longer, but quickly discovered the speed of the system’s two-step (nail and tape) installation during on-site training. “Now I don’t think I could get them to go back to the old way,” Davis says.

That efficiency shaved up to a full day off the framing schedule. “One day costs our organization roughly $1,800 to the bottom line,” Davis says. “If you can pick up five days [over the course of a build], that adds up,” and enables greater profitability.

In addition to reduced warranty calls and costs and installation efficiencies (including not having to implement extra air-sealing measures to meet code-mandated envelope tightness), Green Brick also no longer suffers fines and reinspection fees for failed blower-door tests. And although the builder’s framers still deploy the same size crews, the ease of installing the Zip system enabled Davis to negotiate a lower price per square foot from those trades. These overall savings, as well as a Huber rebate program, more than balance the up-front cost premium.

Like Huber’s Zip system, the insulated precast concrete wall panels from Superior Walls, in New Holland, Pa., combine familiar products to reduce construction time and costs while delivering better performance.

Created in the early 1980s by Mel Zimmerman, a home builder in Lancaster County, Pa., looking for a more reliable solution than concrete block for building full-height basement walls, the Superior system integrates a 1 ¾-inch-thick precast concrete wall and stud bays with foam panel insulation in the cavities. The studs are predrilled for mechanical runs and faced with steel furring to fasten interior finishes. That’s three phases and trades in one.

The system is guaranteed not to leak or crack like CMUs or poured-in-place walls, but the real kicker is time savings—and not just from the product’s integration of typically disparate materials. The system sits on a level 6-to-8-inch-thick bed of crushed stone—no forms to set or pull, no footings to pour. And, no masons to hire; instead, a certified Superior Walls crew handles the on-site assembly.

That was enough to convince Garman Builders to take a shot at using the system a decade ago, and it didn’t take long for the Lititz, Pa.-based builder to fully convert from block and poured foundation walls. “We can dig a hole today, Superior can set up the walls tomorrow, and the [above-grade] framers can be there the next day,” says Mike Garman, president of land acquisition, development, and sales.

The concrete panels cut Garman’s cycle time by a week and enable the builder to set foundations during the winter when temperatures are too cold for pouring concrete. “In the world we live in, cycle time is king, and this system saves time,” Garman says. “There’s far less labor compared with cinder-block foundations and there’s not much of a learning curve. It’s not an overly complicated system at all.”

And while the Superior Walls system costs a bit more than hiring a foundation crew to build the forms, pour and finish concrete, and then strip the forms away, the walls’ guaranteed leak- and crack-free performance and the current shortage of skilled masons make the overall cost comparison no contest. “When you can guarantee the buyer that the walls won’t leak, it’s an easy sell for us,” Garman says. “The walls look much better to the consumer and the cost savings from the labor and cycle-time point of view are a big deal.”

Precut Package Comeback: Precision Framing Honed by Software

Arguably the least-disruptive solution to conventional stick-framing is the reemergence of the precut package, a modern-day version of what Sears, Roebuck and Co. used to ship for homes purchased from a catalog in the early 1900s.

Also known as precision framing or frame-by-numbers, today’s precut packages are honed by software that redraws house plans into 3D designs, corrects errors in the architectural plans, programs cuts to perhaps a 1/16-inch tolerance, and labels each stick with an inkjet printer.

The primary difference in the field is, of course, cutting. Noise from a precut framing jobsite sounds different. The pop of nail guns remains plentiful, while the whir of a circular saw is only occasional. Precut packages logically reduce the estimated 600 cuts required for a typical framing job (and the measuring and marking that goes with them); there is also the waste in material, time, and money resulting from that old-school approach. Typically, precut bundles are packaged by framing sections and stacked on the delivery truck to be unloaded in sequence on the jobsite. Framers open a bundle, sort, and lay out the pieces; spots for nailing the studs are labeled on the top and bottom plates for easy reference and accuracy.

A 2017 McKinsey & Co. report titled "Reinventing Construction Through a Productivity Revolution," noted that globally, labour-productivity growth in construction has averaged just 1 percent per year over the past two decades, compared with 2.8 percent for the total world economy, and 3.6 percent in manufacturing. Clearly, the construction industry is ripe for disruptive technologies to improve a static model that's lagging behind other industries.

“It’s designed and built the way it was intended to be, not based on an interpretation by the framing crew,” says John Osborne, Building Materials and Construction Solutions’ VP of national accounts and innovation, about the Raleigh, N.C.-based lumber dealer’s precut framing system launched in 2013. “Waste reduction is huge, in both framing material reduction and with dumpster haulaways.”

Joe Loidolt, president of Classic Homes, was leery when BMC approached him about using its precut, prebuilt Ready-Frame product. Burned in the past by factory-built wall panels that wouldn’t fit in the field and had to be taken apart and rebuilt on site, the Colorado Springs, Colo., builder agreed to test Ready-Frame on the condition that BMC have a sales rep present when the packages arrived on site.

Nearly four years later, Classic has used Ready-Frame for 150 houses and Loidolt plans to roll it out to the company’s entire lineup of single-family detached and duplex homes that make up the 600 units it closes annually. “We pay a little more money for the Ready-Frame package, but we’re making up a lot of it with fewer VPOs and orders for extra material,” Loidolt says. Another benefit: A clean jobsite. “There’s way less lumber scattered around.”

Loidolt also credits BMC for listening to his contractor’s preferred framing sequences and loading bundles on the delivery truck in that order. And while he suspects his homes are getting framed in the same amount of time as they would using traditional sick framing, it’s probably with one guy less on the crew.

To date, Loidolt hasn’t asked his framer the obvious question, but he’s realizing other, perhaps equally important, benefits. “We’re not asking for any kind of discount from the framer to use Ready-Frame, but we realize we’re probably keeping more framers working for us than going somewhere else and perhaps keeping them from asking us for a price increase,” he says, noting that Ready-Frame jobsites have noticeably smaller crews and occasionally a foreman. “From a labor-shortage perspective, it’s definitely a benefit.”

Home Builders Taking a Design Approach to Reducing Construction Costs

As PulteGroup’s Centex brand strives to grow its market share of first-time buyers with more affordable and moderately priced product, company architects and procurement managers are taking on the task of reducing construction costs. “It’s harder to find opportunities to do that in product and labor, so we’re trying to simplify our product,” says Rhett Yeary, PulteGroup’s national design manager.

While the No. 3-ranked Housing Giant continues to kick the tires of alternative building systems such as modular, precut framing, and panelization, the PulteGroup team also is investigating what Yeary describes as “modular types of components.”

For instance, what would be the impact on the building cycle if the same kitchen layout was used from house to house with prefabricated counters and cabinets? How about prefabricating stairs so the parts are included in the framing package ready for assembly or attachment at the jobsite? Another option could be breaking down heating and cooling by component, specifying the same mechanical unit in a same-size HVAC closet across multiple floor plans.

The potential savings for PulteGroup’s even-flow scheduling goals are compelling. If simplifying a home’s layout or using certain components can reduce the framing phase to the same number of days as drywall installation, the building cycle becomes more “even” (and shorter) because the drywallers aren’t waiting for the framers to finish what typically is a much longer phase of construction.

Along with scrutinizing products and systems that promise to consolidate or eliminate construction steps and days in the field, PulteGroup is analyzing the true savings from using alternative methods, such as whether preinsulated wall panels will yield significant savings compared with a separate crew hired to insulate the framed walls. Or, if stair parts are prefabricated, whether the framers deploy a smaller crew or less-experienced and less-expensive workers to handle that duty? If a home uses a precut, ready-to-frame lumber package, is there really a savings if a high-caliber framing crew is still needed on site for sorting and assembly?

“Ten or 12 years ago, you had an assembly tent in a community where sections of the house were prefabricated on site,” Yeary recalls. “[Prefabricating off-site] is an intermediate step, but panels still need to be componentized, not only so that shipping is cheaper, but to get us as close as we can get to saving money by not having the trades on-site.”

See More of the 2019 Housing Giants Report

WHEELIN' AND DEALIN'—SIGNS OF A SLOWDOWN: Last year was a high-water mark for M&As among home builders, but experts say the industry is on the cusp of a slowdown

STRETCHING OUT—DIVERSIFICATION FOR THE MIDDLE: Diversification as a way for midsize production builders to compete with their bigger brethren

THE LIST—2019 GIANTS RANKINGS: The largest builders, ranked

Access a PDF of these articles in Professional Builder's May 2019 digital edition

Rankings and articles about Housing Giants from previous years