When consumers buy a new car or cell phone, they expect it to be innovative and available with the latest updates. It shouldn’t be any different with new homes, believes Frank Vafaee, CEO and founder of Proto Homes in Los Angeles. After three years of research and development, Proto is rolling out homes produced by a patent-pending, hybrid prefab building system. The company plans to take this system nationwide and, ultimately, worldwide. At press time, three homes had been built and seven more were in the design process.

We asked Vafaee to share his vision with DI, along with Melissa Salamoff of Salamoff Design Studio, Burbank, Calif., who is collaborating with Proto Homes on interior design.

DI: What makes the Proto Homes building process unique compared to other types of prefab housing, such as modular homes?

Vafaee: Modular homes are almost entirely prepared in the factory, shipped to the site, and bolted down. There may be some finishing touches done on site such as siding and roofing.

At the other end of the spectrum is what we call “bucket of lumber.” A good example would be what Sears Roebuck & Co. started doing in 1910 or so, when they would ship you all the materials to be assembled on site. A current example is Lindal Cedar Homes; you select one of their plans and they send you all the posts and beams and other materials.

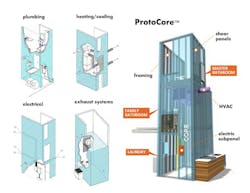

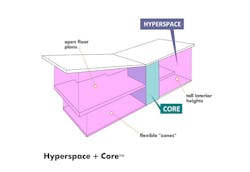

We fall smack in the middle, which is why we call our system hybrid prefab. We’ve broken the house down into two components. One is the Proto Core, the engine of the house. The Core is 8 feet wide, 8 feet long and 22 feet tall and encompasses mechanicals, controls, HVAC, water heating, plumbing and electrical — everything that makes the house run. The toilets are wall-mounted and already installed.

The Proto Core is surrounded by the Hyperspace, or living area — a big, open space enclosed by wall and roof panels. Our panels are tall and designed for balloon framing, rather than the more typical platform framing.

The Hyperspace and Proto Core are shipped to the site and bolted together. Each component is designed to fit into a shipping container so it can be shipped overseas.

DI: What about doors, windows, cabinets and exterior finishes?

Vafaee: Those are all shipped to the site in their own packaging. Cabinets are made in the factory and bolted to the framing.

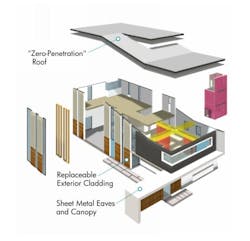

We look at the skin of the buildings as modules that can be removed or replaced any time during the life of the structure. Our cladding material is either corrugated steel or PVC panels that are made in the factory and bolted to the peripheral walls. Customers can also select EcoClad panels, a bio-composite siding that’s made in Seattle.

DI: So in a sense, you’ve componentized the house.

Vafaee: Exactly. The construction process, for us, is not sawing, cutting or honing. It’s basically taking the components that are prepared in the factory and assembling them, pretty much like a LEGO set.

DI: What about the stability of the structure, especially in an earthquake?

Vafaee: We use engineered wood in all of our framing, which gives it a long life span and makes the home very stable. Of course we meet local building codes for seismic reinforcement, but the homes are actually more earthquake-resistant than typical houses. Our roof assembly is all steel and can take a greater amount of shear than wood. There’s no attic and no penetrations for vents or ductwork (those are in the side walls).

Also, with balloon framing your walls tend to shear in one direction. Once you support them in mid-span, the walls act almost like flagpoles and take shear in the other direction too. The box is far more stable and rigid and it’s top light, which performs far better than typical platform framing.

DI: Who designs the homes? Do you use outside architects?

Vafaee: We have eight architects in house. As part of our business model, we’re thinking about offering our system to outside architects, but we haven’t done that yet. It’s something we might start doing in the next few years.

There are limitations to what we can do architecturally. We cannot produce a Cape Cod house or a Georgian house or a Mediterranean house. The system is meant to create a modern house. That said, each house is customized to fit the site and the requirements of the client. We do not have a standard model that we just stamp out.

We don’t use wood, stucco or stone on the exterior because those materials can’t be panelized. One square foot of stucco weighs more than one square foot of framing. For us, it doesn’t make sense to clad a framed structure with a material that’s heavier than the frame itself. And no matter how you install it, condensation always gets behind the stucco and damages the wood. Part of the reason we can’t do a home with a Mediterranean or Italian villa look is because it relies heavily on stucco.

We use a rain screen, meaning our waterproofing is separate from the cladding and the building can be re-skinned easily.

DI: Are there other limitations, such as square footage?

Vafaee: As far as exterior shape and form goes, anything rectilinear is fairly easy. For instance, the home can be L-shaped, cross-shaped or square. Our panels do not allow us to do curvilinear forms. Also, we can’t build anything less than 600 square feet or more than 4,000 square feet. The homes are available in five standard sizes within those parameters.

DI: But the interiors are quite flexible, correct?

Vafaee: Yes, there’s a lot of flexibility in the interior configuration. Double-height ceilings connect the first and second levels to create the feeling of one inclusive space. Each plan allows for an open, livable flow by designating adaptable zones in the home. Homeowners can upgrade the second floor from two to three bedrooms just by moving walls and storage units, which are on casters. Even the kitchen island floats on casters.

There are no stringent requirements for the installation of interior finishes. As long as you can tack it to the stud walls, you can use it.

Interior designer Melissa Salamoff used blue and green accents to warm up the neutral palette of this great room. Salamoff wrapped white Corian countertops around the refrigerator and island for visual interest.

DI: Melissa, how does your interior-design experience mesh with the work you’re doing for Proto Homes?

Salamoff: I come from a commercial background. My first position was as designer of hotel and retail projects in Tokyo for Walt Disney Imagineering. I’ve also done library renovations and residential projects such as condominiums and single-family homes.

Right now my focus is multifamily development—designing the units and public spaces.

The open-office concept is now moving into residential interiors, and we need flexible, innovative solutions. With Proto Homes, it’s about finding products that aren’t insanely expensive and finding ways to make them unique and beautiful.

I do a lot of research and utilize my knowledge of lighting design and commercial products such as sealed concrete floors, big porcelain tiles and cork products.

Vafaee: We were looking for a designer who could create the interior canvas for our homes — one who would carry out the Proto philosophy and expression within the home — and Melissa fit the bill. She came up with bold and inventive solutions that fulfilled our goals.

Tall walls built around a central core create interiors with double-height ceilings and open spaces that can be configured (and reconfigured) according to the homeowner’s needs. Photos: Val Riolo

DI: Melissa, tell us about specific approaches have you taken with the Proto homes that have been built so far.

Salamoff: The spaces are very clean and pure, but stark-white, modern rooms can appear cold. Lighting is very important to warming up a space. I used different sconces and pendants as well as uplighting and other tricks to create more interest.

I also used white tile that has some texture for interest and play. The cabinet finishes have a nice, warm grain and a lot of movement.

The base palette of the Proto brand is pretty neutral — whites, grays and a little bit of wood — but it always has a pop of color in selected places. [For the home pictured here], I used some blues and greens as an accent. There’s a bold pop of sea blue in the kitchen. In the bathroom, the vanity is mostly white with just a little wood and a bold stripe of blue.

Working with Proto presents a lot of great opportunities. Frank and I collaborate on ways to use simple materials creatively. For example, in the kitchen there are white Corian countertops that wrap around the refrigerator and the island. I’ve never seen anything like that in a kitchen before.

The warm grain of the wood cabinets and a dash of blue on the shelves contrast with the white-tile backsplash. The floors are sealed concrete.

DI: So, Frank, what are the benefits of utilizing your system to build a house?

Vafaee: A typical custom-built, modern house in Los Angeles would take about a year and a half to complete and cost about $350 per square foot. With Proto Homes, once the permit is issued (that’s usually the biggest bottleneck), it takes four weeks to produce the components in the factory. Then they’re delivered to the site and the house is completed in four to five months, at a cost of $200 per square foot. Those are real numbers. The client doesn’t have to pay additional architectural and engineering fees; they’re included in the $200 per-square-foot price.

We build only on urban infill sites. With most modular homes, you need huge cranes to set the modules. Our components are much lighter so we need only a small crane, and not a lot of staging room.

DI: Who assembles the components on site? Do you have your own crew or do you use local builders?

Vafaee: Right now we have a contractor of choice in the Los Angeles area. In eight or nine months we’ll start expanding that operation so we have a network of contractors all over the United States. We’ll bring them into our factory for a two- or three-day seminar to show them how the system goes together, and then we’ll certify them. That’s how we’re going to propagate the Proto Homes concept throughout the nation and hopefully abroad.